On 2nd February my colleague Lyn Davies led a party of five on the Irfon at Cefnllysgwynne, among the first fishers to take advantage of falling river levels. They took 14 small grayling, mostly on nymphs fished under an indicator, which is encouraging as there has recently been a noticeable lack of shots on this beat. “Warmer…and a feel of spring in the air,” commented Lyn, ever the optimist. We had snow drops out and lambs in the sheds by this time, but Lyn was a little early there I fear. As you might expect during February the weather was predominantly cold with daytime temperatures hovering not far above freezing most of the time. For many days we saw no sun at all. Richard Park from Warlingham with a couple of friends fished the main river at How Caple Court and shared an 18 pounds pike, a perch and a chub between them. Bretas Vilenus with a friend fished the Bargoed Park Lake and they had a brace of trout each.

Early spring Cefnllysgwynne - Lyn Davies

Early spring Cefnllysgwynne - Lyn Davies  Brew time at Cefnllysgwynne - Lyn Davies

Brew time at Cefnllysgwynne - Lyn Davies I spent a couple of frosty mornings on our Forest Pool which at the moment contains some unusually large rainbows to over 5 pounds and they are in fine overwintered condition. These silver specimens are not wild fish of course (excepting always a few native brownies which manage to spawn in the inlet stream and grow on in the lake), but it’s still exciting to have your line stripped out to the backing. As the water cleared of its colour, black lures no longer worked as formerly, but a little copper wire Pheasant Tail Nymph fished with a floating line and a long leader produced a few confident takes followed by dramatic runs.

Meanwhile the rivers too were slowly clearing as the levels came down. Martin Kellet of London had 3 grayling from the Eyton beat of the Lugg on the 5th while Rob Hudson from Leamington Spa took 5 from the same beat a few days later. Paul Jones from Swansea scored 6 at Cefnllysgwynne on the Irfon. Glen Edwards of Ashford experienced access problems while fishing the Irfon at Melyn Cildu. There is a lack of stiles across barbed wire fences on this beat, so that you have to keep dodging back and forth across the river to make your way upstream.

Philip Archer from Bristol with a friend fished at Monnow Valley, but while the water was still high found it very difficult to access the steep lower banks of this rather wild beat. Even when the water level is normal, you can only wade in certain places here. The top part of the beat where banks are lower was slightly easier, and here they picked up a brace of nice grayling. Derek Goode of Pontypridd with a friend shared 15 Wye chub at Middle Hill Court, and they took 8 more at Fownhope 5 the following day. A discussion of safety while sliding around on muddy Wye banks led to a suggestion that fishers could try wearing crampons. There was a time when anglers could buy a set of chains with rubber straps to stretch over boots in much the same way that snow chains are fitted to car tyres. Mine have disappeared somewhere over the years; does anybody know if you can still buy them? Ben Andrews of Epsom with 3 friends also fished at Middle Hill Court and caught 5 chub to 4 pounds 12 ounces plus a grayling. At the Rectory co-owner Louis Macdonald Ames is engaged on a winter barbel campaign, an interesting experiment for the upper river, but couldn’t quite make contact despite various tentative bites experienced on the 11th. A few more fish were contacted here and there: a Bristol angler took a pike at How Caple Court, another took a grayling on a Perdigon nymph at Aberbwtran, while 3 grayling taken by a Herefordshire angler at Skenfrith included one the dry fly. Llyn Davies fished the Fiddlers Elbow to Abercynon stretch of the Taff, a stretch known for its grayling, but warned that the wading on large boulders is very difficult. Alex Lamb from London took a brace of grayling on a Hare’s Ear nymph from Abbeydore in the Golden Valley, which by the way is one of the most beautiful small stream beats on the whole system, but difficult to fish.

Aberbwtran Irfon - W from Ludlow

Aberbwtran Irfon - W from Ludlow  Cefnllysgwynne - BW from Herefordshire

Cefnllysgwynne - BW from Herefordshire Richard Bradbury from Bromyard fished at Eyton and wrote: “Just fished for an hour after a great lunch at the Corners Inn, Kingsland. At 81 years old I’m finding some beats very challenging for my limited mobility…Lovely beat and friendly farmer.” Richard did manage to catch a grayling during his post-prandial fishing. The thought comes to me that it is a couple of years now that the suspension footbridge at Eyton has been wired off and declared unsafe. This being confined to one side of the river very much restricts the amount of fishing available, particularly in winter. The footbridge carries a public right of way, the bridge is in law considered to be part of the path, and therefore, if I read the regulations correctly, Herefordshire County rather than the landowner is responsible for maintaining it. The notice on the fence keeps extending the closure for 6 months at a time. About time they got on with it then!

Fresh winds and rain arrived from the Atlantic and the Irfon and Monnow were the first tributaries to rise. At Fownhope 5 Chris Duller from Ystrad Meurig picked a place on the bank sheltered by trees from the SW gale and had a great day catching 20 good chub, 5 of which were over 5 pounds. He was unable to tempt the barbel, however. Not so Gerald Allsopp from Bristol who had 2 barbel on small pellets at Middle Hill Court, along with a chub. By the 20th we were experiencing air temperatures in double figures, water temperatures followed and the barbel started to move. Gavin Piper from Basildon fished at the Creel on the 21st and caught 4 barbel and 10 chub as a “…rising river and a warm spell woke the fish up, all to a feeder fished with various baits in gale force winds and rain.” James Allwright of Hereford recorded warm and coloured water at Whitney Court where he caught 6 barbel to 9 pounds 10 ounces and a number of chub to 4 pounds 12 ounces. By the following day the river was dropping slightly and Gavin Piper was able to take 3 barbel and 4 chub at Lower Canon Bridge, while an angler from Banbury took two more barbel at the Creel. David May from Yanworth in Gloucestershire with his grandson Henry fished at Middle Hill Court for 5 chub and a grayling. Henry’s chub were 4 pounds 10 ounces and exactly 5 pounds. Gareth Lewis from Abergavenny had 4 chub from Foy Bridge and Dave Sergeant from Rugby with two friends shared 4 barbel from Middle Hill Court. IJ from Exeter had a single 7 pounds barbel on spam from Holme Lacy 3 and Lechmere’s Ley while Tony Double from Chelmsford with a friend recorded 6 barbel from Fownhope 5. David Williams of Lutterworth with two companions also shared 6 barbel at Middle Hill Court and noted that many swims now have safety ropes fitted. Following even more heavy rain which quickly raised levels, Simon Craig from Hull caught 4 chub in the edge at Middle Ballingham and Fownhope no 8, which he described as difficult fishing.

Flood fishing at Holme Lacy 3 and Lechmere's Ley - IJ from Exeter

Flood fishing at Holme Lacy 3 and Lechmere's Ley - IJ from Exeter  Middle Hill Court - Gerald Allsopp from Bristol

Middle Hill Court - Gerald Allsopp from Bristol  Oldcastle Monnow

Oldcastle Monnow Dwellers in the Monnow Valley (which is surely one of the “quietest places under the sun” if I can be allowed to borrow from AE Housman) have been disquieted by plans for a music festival to be held during June at Oldcastle. Here is a most beautiful stretch of river, closely overlooked by the Black Mountains and which I think actually forms the border between Herefordshire and Monmouthshire. I know this water because I am lucky enough to be invited to fish it now and then. Normally I never see a soul, which is a big part of its charm. It’s one of the last places I still see hatches of iron blues on cold spring days. The shallow gravel bottomed stream with no fencing is surrounded on both sides by a huge open cattle pasture and I can clearly see why festival organisers might have chosen the place. Apparently thousands of attendees are expected over three days, both sides of the Monnow will be used, there will be motor homes, caravans, toilet blocks, a stage, two temporary bridges over the river to accommodate all this, alcohol will be sold until 4 in the morning…need I go on? The whole operation of setting up, taking down and final cleaning up will take two weeks.

You might ask yourself what is the harm if the stream is not polluted and the inevitable mess is removed at the end? Well, that assurance in itself takes a lot on trust. I’m worried enough already about trout and grayling stocks on the Monnow and the river will be full of swimmers. The quiet of the valley will certainly be disturbed for two weeks to the discomfort of people who live nearby or who would like to fish. Local residents who might put up with a single disturbance must be aware that if the festival is permitted once and is successful, it will very likely become an annual event. I quite enjoy live music myself (although I confess that even when younger I didn’t do the Isle of Wight or Glastonbury). However, why here in this lonely place rather than in a theatre or sports stadium? If an open air setting for thousands of visitors to enjoy themselves is needed, why not somewhere already busy with people and already public property such as the Abergavenny Town Meadow or the Monmouthshire showground, respectively beside the Usk and Wye? Glanusk Park near Crickhowell has a long tradition of hosting events. Comments and objections are supposed to be in by the end of February – which didn’t give me much time to think about this – but if you have a view why not contact the Monmouthshire planning authorities. Am I a crusty old misanthropist steeped in nimbyism, selfishly determined to keep this beautiful countryside to myself and friends? My children tell me I am.

The latest news about this project is that a Monmouthshire planning hearing has been delayed in order for the applicants to organise legal representation for themselves.

Monnow trout - olive upright feeder

Monnow trout - olive upright feeder  Monnow Valley below Oldcastle

Monnow Valley below Oldcastle For those following the “Uncle Peter’s War” story from last month, more letters from Finland:

“Thursday 21/3/40, Lapua

RW Burch No 362, KPK 16, 4934, Finland

Dear Margery,

First of all note my new address. We had reached Tornio, I believe, when I wrote last. This wasn’t the end of our train journey by any means, for after spending the night in a cinema in Tornio, we again entrained in the morning at 9am. Our course was across the Gulf of Bothnia and down the east side until we reached our base at a small town called Lapua, which I think is the same as Lappo on the DT map, our lat. 63 degrees North. The journey was a very slow one, due to the congestion caused by troops and returning evacuees, which meant that there was very little food available. Still we did arrive at last. The small party who came out from England before us had got our barracks pretty well prepared, so we are quite comfortably billeted.

The following day the CO gave us what information he could on the general situation [armistice now existing between Finland and the Soviet Union, signed 13th March]. It seems that no one knows whether or not our agreement still stands. Martial law exists in Finland which seems to complicate things a little. The CO saw the Finnish High Command about 2 days ago and they expressed an opinion that some of our contingent might need to return home at once, for whom they would try and arrange transport as quickly as possible, but that important work could probably be found for those who remained. The position is still obscure and there are many factors to be taken under consideration when arriving at a decision. The development of Finnish Russian relations will naturally have a big effect. I am waiting for things to clear a bit before deciding. I am quite enjoying things here now that we have settled down to routine. We have mattresses and sleeping bags and the food though a trifle scanty is quite good.

Here is a further instruction we have received, for letters addressed to us here. In addition to the address given earlier on the letter, put Kenttapostia in the top right hand corner of the envelope and your name and address on the back. Our town, Lapua, must not appear in the address…I must post now, so goodbye for the present. Love, Peter”

I have to sympathise with Peter: to rush across Europe as a volunteer, even a desperately needed volunteer as it was being portrayed in England, to a conflict which ceases while you are travelling, must be frustrating. Peter is really taking it very well. However, some momentous events are about to occur, although Peter and his comrades seem to be unaware of the risks. His next letter is dated two days later and by now a certain disillusion is creeping in:

“Saturday March 23rd 1940

Dear Margery,

Our stay at this base has now come to an end and we are on our way home although I am afraid it is going to be a lengthy business. Yesterday we were visited by a Finnish General, from Helsinki, who had to decide on the future of our contingent. He reviewed the troops and spoke a few words in very broken English, just thanking us for volunteering. Later in the day our CO explained the position. The Finnish High Command asked for volunteers to form a frontier guard (no terms of service) and for civilian volunteers with technical qualifications, although here again they would not even give a promise of any employment. I had an interview with the Air Force recruiting officer. He explained that they had no facilities for giving any instruction, and that only people with service experience who could at once undertake patrol duties were of any use. He was very apologetic about it, and said that the interviewers at Thorney House had no authority to make such misleading promises. This was a set-back, as you can well imagine, and as a result I have joined a big squad who are returning. I have some surprising news for you about whole expedition when I return.”

The actual return journey started Saturday night, with a two hour wait for a late train on a small open station with the temperature at minus 15 degrees C.

“Sunday morning 24/3/40

We travelled all night on quite a warm train and had an interesting conversation with two young Finnish soldiers just returning on leave from the Isthmus. I managed fairly well with my phrase book helped out with frequent sketches. At 12 midday we reached our destination, a small Finnish town near the top of the Gulf of Bothnia. The trains are very few, are up to 5 hours late, while every station is congested with refugees and troops, and many have to be left behind. Although the carriages are warm, the double windows are encrusted on the inside at the bottom with ½ inch of ice, while as a result of the lack of water I have now perfected a means of shaving, washing, doing my teeth and gargling on 1 pint of water which I carry in a lemonade bottle. The lavatories on the train are so cold that the shaving brush freezes. We were moved out of camp in such a hurry that our passports could not be attended to, with the result that we are stranded in this little town while our passports travel down to Helsinki to be stamped and back again. I am sending this letter by airmail and shall not write again as there will be little further opportunity of sending letter by this means, and I shall probably get home as quickly as the ordinary post. I expect we shall take a further 2 or 3 weeks from the date of this letter.

Conditions are quite comfortable here, we sleep in barracks and are fed by the Finnish Women’s Labour Service. We are experimenting with the various winter sports – I have just invested in dark glasses as the weather is very fine and the glare from the snow very painful. We received no letters at the base, so that any that might arrive from now onward will be sent back to England. Hope you are all well. Love, Peter.”

Events would prove Peter to have been quite an optimist. It would be a long and slow road home.

“Kemi, Finland 4/4/40

Dear Margery,

As you see from the address, we are still kicking our heels in Kemi. During the past four days however things have begun to sort themselves out and chances of getting away fairly soon are now better. When we first arrived, we were a body of “forgotten men.” Our passports were mislaid in Helsinki; the British Consul said he could not help as we were under the command of the Finnish Army; and none of the army people at Kemi seemed to know anything about us. Now we have got our passports back duly visa-ed for the journey, and have made contact with the appropriate Finnish authority who seem anxious to get us out of the way as soon as they can.

The money for which I wired on Friday arrived on the morning of Monday – and was most welcome. I am most grateful for the ready response and to James, who I believe, handled your end of the business, judging by the fact that the reply was addressed to Peter Burch. I hope this demand of mine did not alarm you, but I could not go into long explanations on the “wire.” At the time I made my request we had not had any pay and I was rather depleted, but since its arrival we have had two lots of pay, so I am now in clover.

Currency restrictions here do not allow banks to change markkas into English pounds, so I had to hawk my markkas around the British contingent offering 2.5% above the bank rate of exchange. By this means I was able to convert all that I did not need for my immediate use into £1 notes.

Time drags very slowly with so little to do. I rise at 7am and although the canteen serves coffee and buns at our own barracks, I and a few others walk the 1.5 miles to the Swedish army mess for a breakfast consisting of numerous cups of coffee and biscuits and cheese. When we get back I shower and do any of the washing and mending of clothes that may be necessary. I am still wearing my old blue suit, and have just had to cut the back out of one of my khaki shirts to reseat its trousers. The morning meal comes at 11.15am, after which we are free until 5.45 when we get supper. I usually spend the day exploring the countryside, walking or on skis which I have borrowed. In the evening I go into either the Swedish or Finnish army canteens, or one of the many cafes, and get into conversation with whoever I can make understand me.

Shopping is a luxury which few can afford, as most articles including food are considerably dearer and the rate of exchange has been moving against the £ all the time we have been here. A labourer here gets about 4.00 – 4.50 markkas a week.

I must finish in a hurry as I am going off with a party of fellows to the cinema, “The Prisoner of Zenda.”

I hope these letters are coming through alright. I am still without any from you. Air mail seems the only way – and though we have no official address as we are supposed to be moving any time, I might get something if you were to write by return, air mail, care of Peter Burch at Kemi as follows: NORDISKA FORENINGS BANKEN, KEMI, FINLAND with your name and address on the back. Hope everyone is well, love Peter.”

That was written on the 4th April. I hope Peter and his friends enjoyed The Prisoner of Zenda at their cinema in Finland, because events now moved very rapidly. On the 9th April Germany launched full scale invasions of both Denmark and Norway. One of the pretexts for the attack on Norway was the Altmark incident and the alleged infringement of neutrality involved. Belgium, Luxemburg and the Netherlands were invaded by Germany on the 10th May. On the same day, Britain occupied Iceland unopposed in an attempt to ensure control of the North Atlantic. The Battle of France between Germany, the UK and France went on through May and June ending in a French capitulation and the evacuation of British troops through Dunkirk. The “phoney war” was well and truly over.

Like it or not, in a matter of days the nations of Europe quickly began to be sorted out into categories: belligerent, occupied, neutral, neutral/belligerent. You might expand that to include armed neutral, benevolent neutral, strict neutral and qualified neutral. Genuine neutrality without bias is a rare thing, as quickly became apparent. The rapid change in the balance of power of the region meant that Norway and Denmark were now German occupied, while Finland and Sweden remained theoretically and officially neutral. However, Germany had long been a close supporter and influencer of Finland (Hitler even sent the Finnish leader Field Marshal Mannerheim one of his famous Mercedes parade cars), while Sweden’s neutrality almost immediately came under immense pressure to allow passage by rail of German troops and raw materials for its war industry. A transit agreement was signed in June 1940 to cover troops, iron ore, ball bearings and many other goods. There was an argument that Sweden should become pro-German “in order to help Finland.” From 1941 to 1944 Finland fought a second war against the Soviet Union with German help. The UK broke diplomatic relations with Finland in August 1941 and declared war on Finland in December 1941 – although no fighting between Finns and British ever took place.

International volunteers may well have concluded that Finland, Scandinavia even, was now no place to be trapped, although we only know officially that the last members of Group Sisu had left Finland by 28th June 1941. Ordinary letters stopped but next came a telegram dated 10th April from Peter in Stockholm. From this I conclude he had managed to cross the border into Sweden at some time during the previous week and was now in a relatively safer position:

“Post Office Telegram – c1500/10/4 Stockholm 32

Burch, Danby Lodge, Yorkley, Lydney, Glos.

Pay KLM Royal Dutch Air Line, London, 485 Swedish kroner fare Stockholm home. Bare possibility return of communications resumed. Am well. Burch Peter, ---Hotel, Stockholm”

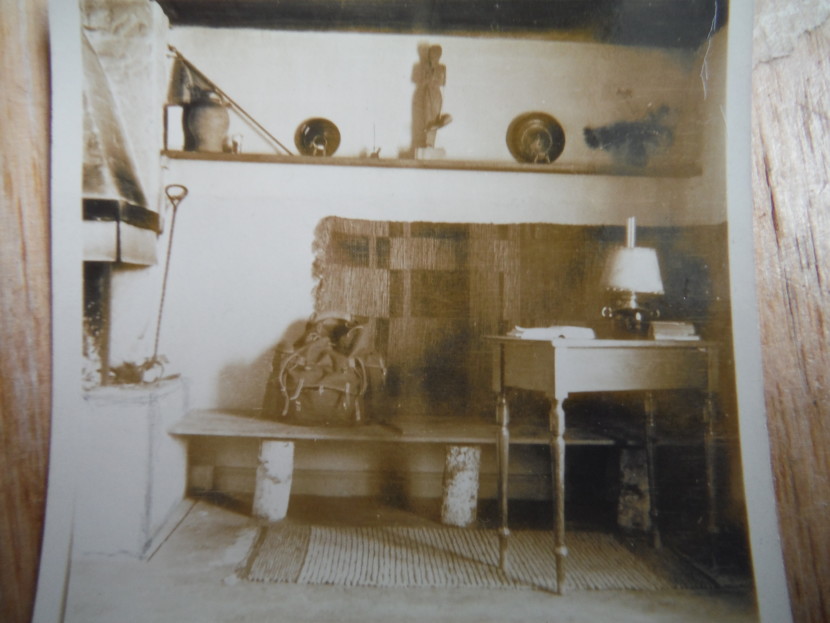

Peter's cottage in the garden of Villa Rastaborg

Peter's cottage in the garden of Villa Rastaborg  Kitchen of Villa Rastaborg, Sweden

Kitchen of Villa Rastaborg, Sweden A civilian flight from Stockholm to London, if not intercepted, would have resolved Peter’s problems wonderfully, but that proved to be a pipe dream. The ordinary infrastructure of Europe was collapsing. There were to be no more letters either, for a long time, although there is a later reference to a fortnightly exchange of cables. The next proper letter received, written to Peter’s mother, comes in August 1940 by which time he seems to have settled down quite philosophically into a gardening job in a mansion outside Stockholm. Meanwhile he stays in contact with the British Legation on the vexed matter of finding his way home. Some of the volunteers had been trying to get out via Russia. Others had been caught in Oslo and interned by the Germans. The letter is accompanied by some small black and white photos, of the one-room garden cottage in which he lives, of the mansion housing the British Legation and of the Special Envoy working in his office. Considering the hundreds of thousands of displaced people which the war has produced by that time, you feel Peter has fallen on his feet. There is no question of internment. And the Swedes, as always, could hardly be nicer:

“24/8/40, c/o PO Fjastad, Villa Rastaborg, Lidingo.2, Sweden. Phone Stockholm 655005

Dear Mother,

I have just heard that one of my friends is leaving for England today via Petsamo [Finno-Russian border] so I am asking him to take this hasty note with him. He is one of a party who are being exchanged for German airmen prisoners in Sweden. I find it difficult to write when there is so much to tell you, but here is the situation briefly. All ports in Finland, Sweden and Norway are subject to German control and impossible for British passengers, and the only way open is via Russia. I applied in June for a Russian visa and was refused, reasons not given. This seemed to close all exits, but within the last few days I have been advised to try again as there is some slight chance of us being sent via Russia and Turkey to Palestine to join the British forces. I think my chances of getting a visa are very slight and I am not pinning much hope on this venture. If it does come off I shall be delighted, but in the meantime I shall carry on my plans for a long stay.

Now about my work, it is nothing if not varied. Fruit picking is the main job just now, but I have about 70 chickens and 10 turkeys to look after. I have to turn the mangle on washing day, there is painting, and I am now being initiated into the business of bottling and preserving of fruits and vegetables. The estate here consists of a large private house with a big orchard and fruit garden. I have a little one-roomed bungalow of my own, furnished with fine antique furniture of country type, there is a spinning wheel, which works, and the fire place is a large open brick one. I have made myself a hammock and am sleeping amongst the fir trees on the hillside, the squirrels often climb down on to my bed. There is a fine lake within sight, so there is plenty of swimming. The gardener, under whom I work, has been out to British Columbia which means I am not learning much Swedish. We get on very well together. I start the day with breakfast at 7, there is coffee and cakes at 9.30, a good lunch at 12.30, more coffee at 3pm, and a good meal at 6.30. It is a long day as you can see and the work is hard, but I am enjoying it as much as I could any kind of work. I have been going in to Stockholm, 6 miles away, on 4 nights of the week, to help with the English course. It has lasted 5 weeks and has just finished. I was acting leader of a discussion group of ten people. It was a very pleasant experience.

Incidentally I am quite well off, my pay as a gardener is not high, about £1 per week with all found, but I now have a capital of £25 in Swedish money. Cannot write more now as my friend is waiting, but don’t worry as I am pleasantly occupied and although I shall persevere all the time with my efforts to get back, I am going to make the best use of my time while I am here. Do take care of yourselves. I think a lot about you and look forward to those fortnightly cables. I am delighted with the fine show the RAF are making.

Love to all. Goodbye, Peter”

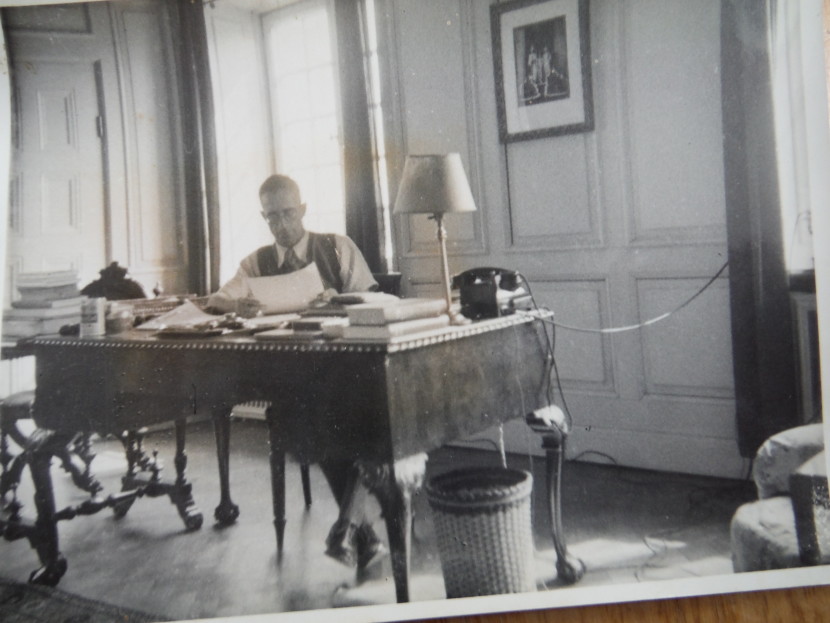

Stockholm - the British Legation

Stockholm - the British Legation  Rear of British Legation, Stockholm

Rear of British Legation, Stockholm Peter was of course referring to the RAF in the Battle of Britain. So how did Peter finally achieve his return to England from Sweden? Of course I have always known that Peter returned, supposedly through occupied Europe in a train, but not how it was arranged. My father might have known something more but there is nobody left alive in the family who has the details, and there are no more helpful letters left by Peter. There might be information somewhere in the UK Foreign Office files, the personal papers of Victor Mallet, then the British special envoy to Sweden, or possibly the national records of Sweden or Germany. There might even be papers in Portugal. However, I had not been able to find any sure information, so I had to rely on conjecture as to who arranged what and with whom.

The conjecture relied on the nature of different nations’ neutrality during the 1940s, on the nature of their ongoing relationships with the belligerent Germany and British Empire, and indeed the strength of the humanitarian imperative, wherever that could be found. Sweden, as is well known, was forced to make major concessions to Germany in terms of allowing passage to troops and war materiel. However, Sweden’s instinctive position was naturally pro-British or pro-Allies. They did what they could. Swedish diplomats during the 1940s also had a very honourable record of negotiating to rescue threatened civilian groups, including Jews. Their German counterparts may well have regarded such small gifts as a reasonable quid pro quo in return for co-operation in transfers of military material and the supply of iron and other valuable goods such as ball bearings, for which the Swedish company SKF had a virtual monopoly. On several occasions during the Second World War it was fully expected that Sweden would be occupied. During early July 1940, the British Legation in Stockholm burnt its files and prepared to move British interests under the protection of the US Legation in case of an invasion. Instead, from July 1940 to October 1941 some 670,000 German soldiers were permitted to transit Sweden to Norway by rail.

In Iberia, the neutrality of Salazar’s Portugal was very different from that of Franco’s Spain. The dictator Franco was a true fascist and until the Hendaye meeting Hitler had hopes of persuading him to join the Axis powers and declare war on the Allies. An instinct for self-preservation seems to have gotten the better of Franco when considering that proposal. Nevertheless the Germans received a lot of lee-way from Franco’s Spain, including the possibility to set up espionage networks. Portugal has always had a natural tendency to take the opposite course from Spain. Doctor Salazar in Portugal was certainly a dictator, but a rather pro-British one, who also personally did a great deal to rescue groups of Jews from occupied Europe. Some say he could have done more, but several hundred thousand refugees were able to pass through Portugal during the Second World War. While continuing to trade with Britain, permitting it use of bases on the Azores and expressing a belief that the war would eventually result in an Allied victory, Salazar also continued to export much needed tungsten and other goods to the Axis powers. At this time humanitarian interventions by Salazar and his railway boss Leito Pinto even resulted in special trains being run between the Portuguese border and Berlin and other European cities. Deals were being made, for war material, for oil, for money, goods, and for refugees and prisoner exchanges. You can understand how many or most of these deals were best arranged on a “no publicity” basis and may not even have been recorded.

Interior of Peter's cottage

Interior of Peter's cottage  Victor Mallet, British envoy

Victor Mallet, British envoy The paragraphs above might explain how an arrangement for a sealed train to run from Sweden to Denmark by sea and down across occupied Europe eventually to Portugal may have been agreed to by the Germans. This “sealed train” was the story given to the family and which I heard as a child. Just consider the implications of an Englishman or a British group making such a journey in 1941! Who exactly organised it and what were their calculations? What was the departure date and exactly who was on the passenger list? The famous sealed train of history, the one everybody knows about, is the train which the Germans used to introduce Lenin from Switzerland to St Petersburg in 1917. In fact Lenin and his party were allowed off to spend a night in Frankfurt. In the case of Peter’s particular war-time journey, there used to be a direct Malmo to Berlin roll on roll off ferry train which continued until 2020. I wondered if Peter travelled via Berlin. In her more lucid moments my aunt, last survivor of that generation, thought that he did. Who were the escorts and the fellow passengers?

After searching on some of the remoter shores of the internet I stumbled on what may be the answer. As well as the Sisu group of British military volunteers, a company of London firemen complete with an engine and equipment had also volunteered for wartime service and set off to Finland at the beginning of 1940. When hostilities ended, they remained and for a while did honourable service fighting civilian fires in Helsinki. Later, at German insistence, they were interned despite some Finnish embarrassment, and later still allowed to cross the border to Sweden. Accounts left by several of the firemen in the group describe British diplomatic efforts, presumably by Victor Mallet, resulting in an evacuation by sealed train which ran from Sweden, Denmark, down through Germany to Switzerland. The journey was continued through Vichy France to the Pyrenees, to Spain and eventually Portugal. The fire-fighter group was apparently accompanied by several British consular staff and - I will hazard a guess - perhaps one British electrical engineer who had been gardening in Sweden for a few months. This looks to me like the final piece of the jigsaw. I do know that during the early spring of 1941 great uncle Peter arrived by train in neutral Portugal, sent a cable and then took ship to England. Finally he arrived in Gloucestershire’s Forest of Dean with his pockets full of Portuguese oranges, to the delight of the family, who under rationing had not seen exotic fruit for a long while.

There is a gap in the letters to grandmother until a group dated 1945. One is from Peter, back in Norway now for the RAF and engaged in supervising the dismantling of the surrendered Luftwaffe. The rest are from my father James, who after time as a flying instructor in what was then Southern Rhodesia, had taken UK leave and then been sent out again by a series of gruelling military transport flights to Singapore, newly recaptured from the Japanese. Once at Changi airfield he was supposed to set up a course of training for night flying, but was kept waiting for arrival of instrument flying hoods. Meanwhile he tried his best to wangle any flying time possible on one of the Spitfires or Thunderbolts kept there. Unluckily for him, his youthful pestering came to the notice of the air officer commanding who figured him for a sporty type and to keep him quiet put him in charge of preparations for a sports day. This mainly involved building a running track and rugby pitch and for this work he was assigned 50 Japanese prisoners of war. I like to think he gave them better treatment than had been meted out to Allied POWs in the years before. All flight training stopped when Japan surrendered, resulting in some pupils who needed only another hour solo to qualify, being prevented from receiving their coveted wings. Father came home by ship, by his account playing cards all the way across the Indian Ocean and up the Red Sea. His bridge partner was one Pilot Officer Wedgewood-Benn, who later became quite well known.

Great uncle Peter never married or had children. His death in 1969 was somewhat mysterious. He was found lying dead in the cabin of a little wooden sailing cutter he had restored, having been anchored for days in the estuary of the Orwell. Like Peter himself and his war-time story, that coming to rest seems to me slightly enigmatic, raising questions as much as providing answers.

We ended February with generally widespread flooding of the rivers, but a change to cold high pressure weather now in prospect. A new season will be open by the time you read this. Tight lines!

Oliver Burch