At the start of the month, we were still unable to fish and I was thinking of renaming this letter “The Lockdown Diaries.” It has been a strange period and, oddly enough, one of the most beautiful springs I can remember. We have at least had the pleasure of much more time spent exploring our own locality and much less time behind the steering wheel. During lockdown I suppose that we have all come to know our own home and garden – if we are lucky enough to have one – rather better. Our house is a fairly new one and, while there are nice views out to the Forest and the estuary, the garden is quite small. At least there is room for a terrace, barbecue, table and chairs and just a few flower beds. On the other hand, fishing pal David Burren and his wife live in a picturesque cottage in a big garden a few miles north of the Forest and he sent me this description of a fine Gloucestershire spring:

“Here in Longhope, the garden and wildlife think it is June. In our garden, we have had incredible blossom on the fruit trees, the blackbirds have been singing, the goldfinches squabbling and the blue tits nesting. The wisteria and honeysuckle are in full flower, as are the Welsh poppies. The pheasant that demands feeding every day, the bat that lives in our porch and flies every night, the toad in the greenhouse, the newts and frog in the pond, and the large and small rabbit that come close to us most days, are all getting on with their lives. The magpies with their young are already hunting. Nature waits for no man. It will be interesting to see if the fish have noticed our absence – I doubt it. I will have missed them more than they will have missed me.”

Hadnock Hill, above the lower Wye

Hadnock Hill, above the lower Wye  Beech hanger above Forest pool

Beech hanger above Forest pool  Forest pool at the Clanna

Forest pool at the Clanna At the beginning of lockdown, there seemed to be a rather pleasant consensus that partisan politics could be put aside and we should all show some unity in the national fight against the virus. It was nice while it lasted, but as consensuses go, it didn’t last long. The much vaunted “war time spirit” was noticeable in the general population, but there was much less of it on display amongst the chattering classes. Some of the left of centre pundits who managed to get themselves heard on television demanded a wartime-style government of national unity, in which members of the opposition would be given ministerial jobs. This conveniently overlooked the recent general election in which the opposition parties obtained a remarkably reduced overall mandate from the public. Why on earth would a government with a strong majority share decision making with an opposition whose policies had proved so unrepresentative of public opinion?

The new leader of the opposition made an early speech in which he stated his intention to be supportive during the epidemic and then proceeded to do exactly the opposite, picking holes in every statement and querying every measure taken by the government. The usual media outlets predictably gave much more space to opposition criticisms than to government statements. Meanwhile the devolved administrations, who of course have the right and responsibility to make local decisions about medical matters, seemed to make a particular point of following a different policy to that of Westminster. The first minister for Scotland helpfully explained to anybody who would listen that she did not understand the words “Stay alert.” One can only hope that the different lines taken by the administrations in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland were based on sound regional scientific advice rather than merely flexing their muscles as some sort of demonstration of a right to independence.

Meanwhile, as England cautiously moved to restarting the economy, the “back to work” message was far from welcome everywhere. One couldn’t help suspecting that some of us had got quite used to being furloughed at home on 80% salary with a mortgage holiday and wouldn’t mind a bit more lying in the sun. Trade union leaders demanded from the government “absolute guarantees” of safety for returning workers. Unfortunately, in the times in which we now live, there are no guarantees of safety at all, only calculations to be made about comparative levels of risk. The end of the month seemed to be entirely taken up with Cummingsgate, which provoked in me some thoughts about what exactly constitutes an essential worker. I can understand why our son with his team is encouraged to roam the country fixing power lines. I can understand why our daughter is allowed to move between military bases and hospitals in England and Wales. But what about the baying pack of investigative journalists unleashed on the highways and byways of the North-East, every one of them tasked with finding out any incriminating information, no matter how minor, about Dominic’s Great Road Trip to Durham? Essential journalism holding government to account? I think I can recognise a political coup attempt when I see one.

Mowley Wood - Seth Johnson-Marshall

Mowley Wood - Seth Johnson-Marshall  Six o'clock on a May morning

Six o'clock on a May morning  Whittern Arrow

Whittern Arrow Lockdown regulations as applied to angling continued to cause confusion. I had always thought the initial rulings made by the Westminster government did not exclude solo fishing. At least that was my interpretation of the wording. It was the politics of our own sport and the fear of social media criticism which kept us off the river as far as I could see, without any visible benefit to the business of fighting the epidemic. A few private owners fished on; otherwise the poachers had the rivers to themselves. On 10th May the Prime Minister specifically mentioned angling as something we might do, using a bit of common sense, during a slightly relaxed second phase. We might also sit in the park. A sensible decision, I thought, and we should always use a bit of common sense. Unfortunately the Welsh government did not agree and confirmed a ban on angling and also on driving to exercise. This created the situation that we could fish from one bank of some of our rivers, but not the other.

The Angling Trust site crashed at once (although later they published detailed advice for England). The WUF notified that their waters would remain closed until the situation clarified. A day later we heard from the Welsh government that fishing would be allowed, but only by local people who had walked rather than driven to the river. Next day, after efforts made by Angling Cymru, the situation had changed again. Welsh anglers would be allowed to drive to the river, but not far – to the nearest river in fact. English anglers could drive as far as they liked to fish in England, but it must be a round trip, no overnight staying, and they must in no circumstances drive into Wales to fish. The WUF opened up their website to book English waters only. I worked out that I could now fish tributaries of the Upper Monnow (in Herefordshire), but to get there I would have to drive the long way round through Hereford rather than directly through Monmouthshire. On the 14th the South Wales police were still informing that no driving to fishing was allowed and that fishing had to end at midnight. No Welsh angler should drive into England.

Lower Monnow, lying fallow

Lower Monnow, lying fallow  Perfect levels on the lower Wye, but nobody allowed to fish yet.

Perfect levels on the lower Wye, but nobody allowed to fish yet. 13th May was the date when some angling began officially in England. By now the rivers were pretty low after more than 6 weeks of drought, so conditions were no longer ideal. However, Richard Woodhouse of Ross Angling Association kicked off with a fine Wye spring salmon of 12 pounds from the Hom Stream at 8 o’clock in the morning. He was using a floating line and an Usk Grub. A couple of hours later, yours truly got into a fish a little way upstream at Upper Loo; this was a small springer which unfortunately let go after a few minutes play. I was using a floating line with a size 10 Bann Shrimp, and I was honestly quite surprised to make contact as the river was so low and full of drifting pieces of silkweed which constantly fouled the fly. We know at least that there are some two sea winter fish in the lower river this year; salmon were also taken that day at Aramstone and Wyebank. The last, by the way, is a highly recommended short piece of salmon fly water just right for a spring morning or evening.

First salmon day on the Wye

First salmon day on the Wye  The Hom Stream

The Hom Stream While in the river that afternoon at Weir End I saw the first massive hatch of true mayfly. On walks by the lower Wye this sunny spring I have also seen good numbers of yellow mays, olive uprights, pale wateries and falls of hawthorn fly, though few fish rose. The 14th was one of those hard, bright days with a cold northerly blowing, but this time the trout anglers took to the water in numbers. CB from Droitwich had 5 from the Lugg at Lyepole with a PTN and Seth Johnson Marshall from the Foundation had a fine 14 inch trout among 5 from the Arrow at Mowley Wood. Look closely at the photograph of this fish and you can just see the blue parr marks, which Arrow trout never seem to lose even in adulthood.

RW from Hereford got a dozen from the Titley beat. AM from Worcester had 8 on dry flies from the same beat the following day. JS from Stourbridge with a friend had a dozen from Lyepole and PB of Gloucester with a companion using parachute dries managed 6 from the Lugg at Dayhouse. On the 16th CH from Bromsgrove with a companion got a very creditable 20 from Chanstone Court in the Golden Valley. JD from London was on the Lugg at Dayhouse that day. He caught 3 trout, but he also caught 4 poachers spinning and worming the middle of the beat, and to make matters worse, found himself in conversation with somebody who thought he shouldn’t be fishing “because of the close season.” The season is closed for grayling of course, but don’t you just love it when you meet a fishing know-all who sees you as fair game for a lecture? AP from Dudley had 10 from the Kington beat upstream, while JA from Leominster had 5 to 13 inches from the Court of Noke while mayfly were hatching. JA was another who had to contend with poachers, in this case two boys with spinning rods and a story.

I think all the rivers have had a hard time of it during the last period. It isn’t very difficult to work out, is it? The combination of a lot of people with time on their hands plus no ticketed anglers on the banks for weeks has made illegal activity almost inevitable. LH from Hereford was on Dayhouse on the 17th and had 10 trout with nymphs.

14 inch Arrow trout, Seth Johnson-Marshall

14 inch Arrow trout, Seth Johnson-Marshall By this time the drought was becoming quite severe and the main Wye started to receive the agreed compensation water from the Elan Valley dams. All the tributaries were in trouble and from what I could see the Usk, available only to local Welsh anglers of course, was really short of water. Salmon catches seemed to be limited to just above the tide on both rivers. Maurice Hudson scored at Cadora Backs, as he usually does in these conditions.

Court of Noke trout - JP from Shobdon

Court of Noke trout - JP from Shobdon  Mayfly spinner - JP from Shobdon

Mayfly spinner - JP from Shobdon  Monnow trout

Monnow trout Regardless we pressed on with an early mayfly season on the available English streams. On the 18th PB from Churchdown with a friend had 11 trout on dry flies from the Lugg at Eyton. AK from Leominster had 10 trout between 6-11 inches from the Arrow at Titley on the following day. PB from Churchdown with his friend reported a difficult day at Mowley Wood in the hot weather, but apparently some larger fish began to move during the evening. On the 20th AM from Hereford was another who encountered poachers, in this case three of them with spinning rods at Hindwell Coombe. I gather nothing was done about it at the time. JA from Leominster fished a rather overgrown Hergest Court for 14 trout. TL from Kingsland had 5 from the same beat the following day and hopefully was able to tell the owner that it needs a trim. RG from Stratford on Avon fished a shrunken Escley Brook at No 4 beat and caught 6 fish. These included a real specimen for a small stream at 16 inches. On the 22nd AM from Worcester had 6 trout to 14 inches during a mayfly hatch at Mowley Wood. AD from Monmouth scored just three while fishing the same beat with mayfly patterns in a gale of wind the following day, but one of these was also a well-conditioned 16 incher. JP from Kidderminster took 8 trout fishing a nymph under a dry fly at Bucknall. I am not sure how many JL from Shrewsbury caught from the same beat, but the photograph he sent in indicates he got his 4WD closer to the Teme than any before him! On the 27th JA from Leominster fished the Arrow at Hergest Court again, this time for 18 trout. DO from Bath reported an extraordinary brown trout of 18 inches taken on a Grey Wulff at Dayhouse. It is not often we see a trout of 2.5 pounds from the Lugg and Arrow.

How close can I get to the Teme at Bucknall? - JL from Shrewsbury

How close can I get to the Teme at Bucknall? - JL from Shrewsbury Poaching is a perennial problem; I have written about it before and no doubt will again. It will do no harm to remind of some key points. Firstly, there is no elite anti-poaching squad of tough bailiffs waiting to be called into action by the WUF on receipt of an angler’s catch return. In fact the main deterrence to illegal activity is the regular presence of legitimate anglers on the bank. NRW and the EA may be interested in lack of licences or illegal fishing methods, but their water policing resources are now minimal. Poaching will certainly ruin your day – if you find poachers on the water the fishing will already be spoiled - but the best time to deal with the problem is then and there. Don’t leave it until making your catch return that evening. If any other rod is entitled to be on the water, the information given you by the WUF will have made this clear. If you unexpectedly encounter somebody else fishing, you should politely ask to see their fishing ticket and be prepared to show them yours. When they fail to show you a ticket, you should ask them to leave. Don’t be confrontational in any way and certainly don’t get into a convoluted discussion. These gentlemen, good bluffers all, do very well out of those who fail to report the offence, which is in fact equivalent to a burglary. If they don’t leave when asked, return to your car and call the police. As an offence under the Theft Act (theft of fishing rights) is ongoing, you are perfectly entitled to use the 999 number when calling. Even if the police are unable to send a patrol immediately, your report must be recorded…insist on it. This in itself will be likely to result in more anti-poaching resources available in future.

The fine dry weather continued to the end of the month and as lock-down restrictions in England were partially lifted, there was something of a rush to the countryside, which gave us an idea of what government has been worried about. The national mood had changed and people by now seemed to have become more nervous and short-tempered about the situation, for which the media presentation of events must bear some blame. Even in our small rural towns we saw more anti-social behaviour…although hardly equivalent to cities in the United States where the National Guard were called out! While Corona restrictions and quarrelsome politics continue to trouble us, I thought I would write about something rather different to cheer us up. So here is an article about foreign travel, which is something which few of us can do at the moment, together with recommendations for some favourite travel books. Reading, at least, is something we definitely can do. One of these is a really good fishing book also, so the piece is not completely off the point. I’m short of photographs to illustrate this one, but I hope you enjoy it.

I’m thinking back now to an idea I had a long time ago for a family camping holiday in Europe – a trip across Europe to be more accurate. The plan was to wangle at least a month away from work and other cares, follow the magnificent Rhine upstream as far as we could, cross the watershed in the recently re-unified Germany to pick up the Danube, then follow it down to the Black Sea. There were going to be some visa complications at the far end, but we would see what we could manage. Things didn’t work out exactly according to the plan, but we ended up visiting 13 countries in our Landrover during that summer of 1991.

We already knew parts of the Rhine system, and initially we headed for Heidelberg in a dream of steep vine covered slopes, turreted castles, sunshine and wonderful white wine in riverside restaurants. The campsites were all by the river with a view of the water. This time I found it was the commercial traffic which fascinated me. I could remember when working barges pulled by tugs were a regular sight on the Thames, but those were nothing like the giant Rhine barges. Six of them would be lashed together and pushed by the tug which included the captain’s living quarters and the family car parked across the deck, usually with a line of washing also.

It was a fine thing on a warm summer night to lie in our sleeping bags with the tent flap open, listening to the muffled beat of heavy diesels and watching the dark shapes pushing steadily against the current. Mark Twain (who of course himself had been a Mississippi river boat pilot) wrote a rather good book about his European travels in which he described the great iron chain which during the 19th century was laid for many miles along the bed of the Rhine. The steam boats of the day, if headed upstream, would grapple for the chain, attach it to a winch and use it to haul themselves against the flow.

Next we cut across South Germany to Ulm, where the great spire of the Minster overlooks the young Danube flowing east. The Donau here is a stream as fast and fresh as the upper Wye and looked, I thought, as if it might hold grayling. It soon grew larger, to match in size and eventually over-match the westward flowing Rhine. The shipping traffic of many nations was even more impressive on this river, which is a truly international water-way. Vienna was followed by the tower blocks of Bratislava, then Budapest, that beautiful double city connected by bridges which I have always preferred somehow to its Austrian counterpart, and then we were out on the great Danubian flat-lands, the weather growing warmer by the day. The year was 1991; the last Russian troops had only just left and Hungary was opening up to western travellers and investment, German businessmen to the forefront. We took a side journey to Lake Balaton, the “St Tropez of Central Europe,” where every beach was packed with disconcertingly glamorous Hungarian women. All of Budapest seemed to be on holiday at the lake and I walked into the only bank I have visited where you could see a whole queue of customers lined up at the counter wearing bikinis. Every open-air czarda restaurant seemed to have a gypsy orchestra entertaining an enthusiastic clientele.

Balaton of course is famous for its giant carp, which fishermen used to take from the reed beds with a trident. Istvan, an old farmer we met in one of the villages, told me how as a young man he had driven a horse and cart 20 miles across the frozen lake in winter. More distractions: we were off to Debrecen and the horse-breeding Puszta. I have always been fascinated by open plains; here the Alfold seems limitless with flat horizons under giant skies, eventually running on into Ukraine, the Pripiyet Marshes, and what was then the recent disaster of Chernobyl. In front of each low farm house with elaborately decorated eaves was the frame of a dipper well with counter-weighted shaft to pull up the water and by one of these we met a goose-girl guarding her flock of hundreds of birds. She looked as if she belonged in a story by Hans Christian Andersen, but a mining town on the Ukrainian frontier seemed to be full of reeling drunks. Doubling back along the border with Romania led us to Pecs with its great Pasha Qasim Mosque, built when the Turks held this territory, then to Mohacs, the last Hungarian town on the Danube. And there we came to an enforced halt.

According to our plan we should have gone then into Yugoslavia, eventually to Belgrade and on to Bucharest. I wanted so much to see the wild part of the lower Danube. It was once a place of legend: the narrow Iron Gates between Yugoslavia and Romania where the flow was so powerful that ships had to be hauled upstream by paired steam locomotives straining stroke by stroke on steel cables; and Ada Kaleh, a remote river island of Muslims where Turkey had retained its last sovereignty in the Balkans.

All this was now gone, submerged under modern hydro-electric schemes. Due to the new dams, the beluga sturgeon of the Black Sea can no longer make their way into the upper Danube. The huchen, a land-locked salmon rather like the Mongolian taimen, is now rarely found (although I later learned they are caught occasionally on Balkan tributaries). On the other hand the giant wels catfish, which traditionally used to be caught with a skinned rabbit presented on a meat-hook, has been preserved as a sports species and exported all over Europe.

However, we were not going to be able to continue following the Danube into Yugoslavia, at least not under present circumstances. A couple of years before I had driven the same Landrover (then brand new) through Yugoslavia in the final days of communism, crossing the pass at Klagenfurt on my way to Greece. The border guards then stamping their feet in the snow still wore long greatcoats and the single red star on their tall grey hats. The main Yugoslav motorway in those days formed one end of the modern version of the Silk Road, with the trucks of eastern nations coming and going at Germany’s back door. Most were Bulgarian, Turkish and Greek, but you could also see the big green lorries of Tehran Transport or even a rare Israeli. This was the road the hippies used to take on the way to India. The country was then gripped by inflation; during a two day drive from Austria to Greece I was paying the motor way tolls with great blocks of devaluing dinars.

All that motorway movement had finished quite suddenly and right now both the road and river traffic was halted. The Danube at Mohacs was almost choked with shipping of different nationalities waiting to go downstream. We watched a Russian-flagged tug with six barges attached come down, turn against the current and drop its anchors in mid-river with a great crash. Later the worried looking master came ashore carrying his papers and went into the office of the Danube Commission. Everybody was listening to the radio. Navigation was closed, we heard, because Serbian and Croatian forces were fighting below us at a place on the river called Vukovar. This didn’t sound like a family holiday, although as it turned out I would spend most of the following decade working in Yugoslavia while the country gradually broke apart in a series of inter-ethnic wars. As it was, we changed our plans and wandered off home via Switzerland, Italy and the south of France.

OK, by now you will be asking yourself what on earth has all this got to do with anything and in particular with fishing? Well, I relate the tale because the inspiration for our drive along the great rivers came from two different writers. One was Patrick Leigh Fermor, who was knighted before he died at the age of 96 in 2011, and who is buried in Gloucestershire. Paddy Leigh Fermor was originally best known for his wartime SOE service in occupied Greece. The book by Billy Moss and subsequent film Ill-met by Moonlight tell the story of the abduction and eventual removal to Egypt by British motor torpedo boat of General Kreipe, commander of Crete’s German garrison. I never met Patrick Leigh Fermor, but he was once kind enough to write me a letter from his home in the Peloponnese, telling me he liked a book I wrote about Crete and its history. Before that I had walked past his villa at Kardamyli, marked on the bare hillside by exclamation mark cypresses, but hadn’t cared to disturb the great man in his private refuge. Then I was at the start of a couple of weeks alone walking with a backpack around the Mani, that strange mountainous peninsula at the remote southern end of the Greek mainland. I left the Landrover at Gytheion and headed south on goat tracks between the mountains and the Lakonian Gulf. There is hardly a tree on the sun-burned Mani; the almost empty villages have only prickly pear. This Deep Mani was once a land of notorious pirates, brigands, Greek patriots and saints, known particularly for its blood feuds and clan wars. Leigh Fermor had known the “Land of Evil Counsel” during the fifties when it still had some population, but in my time it was still very beautiful, not unlike parts of the Cornish coast, but by then a largely deserted place of ruined fortress towers, jewel-like Byzantine churches and ghosts. Everybody had gone away to Athens or Melbourne. Mostly I slept on the beach. Today, surprisingly, there are a couple of hotels.

While researching for my book I did have the privilege of meeting, in their own old age, some of Leigh Fermor’s wartime comrades from the resistance on Crete, including the delightful George Psychoundakis, the famed “Cretan Runner.” Times had changed, as they usually do. There were always mixed feelings on the island about the wisdom of the Kreipe abduction. For one thing the wrong general had been captured. Kreipe himself was new to the command and by all accounts rather a decent man. Afterward the loathed General Muller returned and the German reprisals under his directions burned a number of villages in the Amari valley and more than 1,000 houses in Anoyia, where all men between 16 and 60 found within a kilometre of the village centre were executed. Anoyia, when I first knew it, was an ugly place of modern concrete houses and a definite preponderance of elderly women living alone. To be fair, the retreating German garrison towards the end of the war had other reasons than the abduction for laying Crete to waste. Kreipe and his English and Cretan abductors made their own peace and used to meet for reunions in Athens after the war. Many Cretans went to work in Germany in later years and by the 1980s German tourists were making up the largest contingent of visitors to the island.

Before his wartime Cretan exploits, Leigh-Fermor had about the most adventurous youth you could possibly imagine. After leaving school (he was expelled from several) he had the romantic idea of “walking to Constantinople,” a journey which he started from London in 1933. Like us (but on foot, the hard and I suppose better way) he headed “up the Rhine and down the Danube,” relying mainly on his good German and learning other languages as he went further east. It took him over a year. On his walk he encountered curiosities of the old Europe and the rise of fascism. He was only 18 when he started, certainly widely read and with all the confidence of youth, but inevitably somewhat politically naïve. Hitler had just taken over in Germany. His encounters there varied between the new party members aggressively keen to pick an argument with an Englishman and the friendliest of people eager to do kindnesses for a wandering student. Further east, helped by a few useful letters of introduction, he met and on occasion fell in love with, the last representatives of a Central European aristocracy which was about to be obliterated, first by war and then by centralised communism. In mainland Greece he witnessed or rather took part in the suppression of the Venizelos revolt (displaying typical Leigh Fermor adventurism, he persuaded somebody to lend him a horse in order to join a cavalry charge, to the considerable displeasure of British Consular officials). And he reached the newly-named Istanbul, as he had always planned, before moving on to Mount Athos.

You wonder how he managed all this, depending on the occasional collection from post offices of five pounds mailed by his father. The fact is that the “right” sort of people were charmed by this wandering English boy and he received a lot of hospitality on his way across Europe. On occasions he slept in barns or ditches, but not so often. Tall and good-looking, he would be liked by women all his life; it seemed natural enough for Paddy Leigh Fermor to turn up at embassy parties with a Cantecuzene princess in tow. Paddy was to be widely, but not universally, loved for his intelligence, charm and enthusiasms and he did very well amongst the chattering classes, before the war and after. The detractors would say he depended on the kindness of wealthier friends far too much and for far too long. He was advised early in his writing career to avoid the millstone of a day job and it was to be the late fifties before literary royalties made him financially independent. When not travelling, he spent much of the rest of his life in Greece where he was regarded by many as a sort of modern Byron. In fact he once tracked down a family who had preserved a pair of Lord Byron’s slippers – you could still see the mark left by the clubbed foot. Books on monasticism (A Time to Keep Silence) and the Carribean (The Traveller’s Tree) were successes during this period and he went on to write two superb books about Greece: Mani and Roumeli. Greece was a natural but not always an easy home for him. The country, divided between right and left, had suffered particularly badly during the war-time occupation and subsequent civil war. The violence in Cyprus and the Colonels’ regime were inevitably difficult times for British philhellenes living among Greeks.

Mani

Mani  Roumeli

Roumeli I think it is fair to say that Leigh Fermor, unlike most foreigners, was not so much interested in classical or even modern Greece, but very much in what remained of Byzantine and mediaeval influences. He was acknowledged as an expert on some of the nomadic shepherding peoples of the Balkans: the Vlachs and the Sarakatsani or “Black Departers” as he described them. At 70 years old (again typically Leigh Fermor) he swam the Hellespont. After all Byron had done it. Towards the end of his life he published two books about his long walk across Europe: A Time of Gifts and Between the Woods and the Water. Unfortunately he died before completing a third, although some notes have been published. Leigh Fermor has with justification been claimed as the twentieth century’s greatest travel writer in English and the biography by Artemis Cooper is recommended.

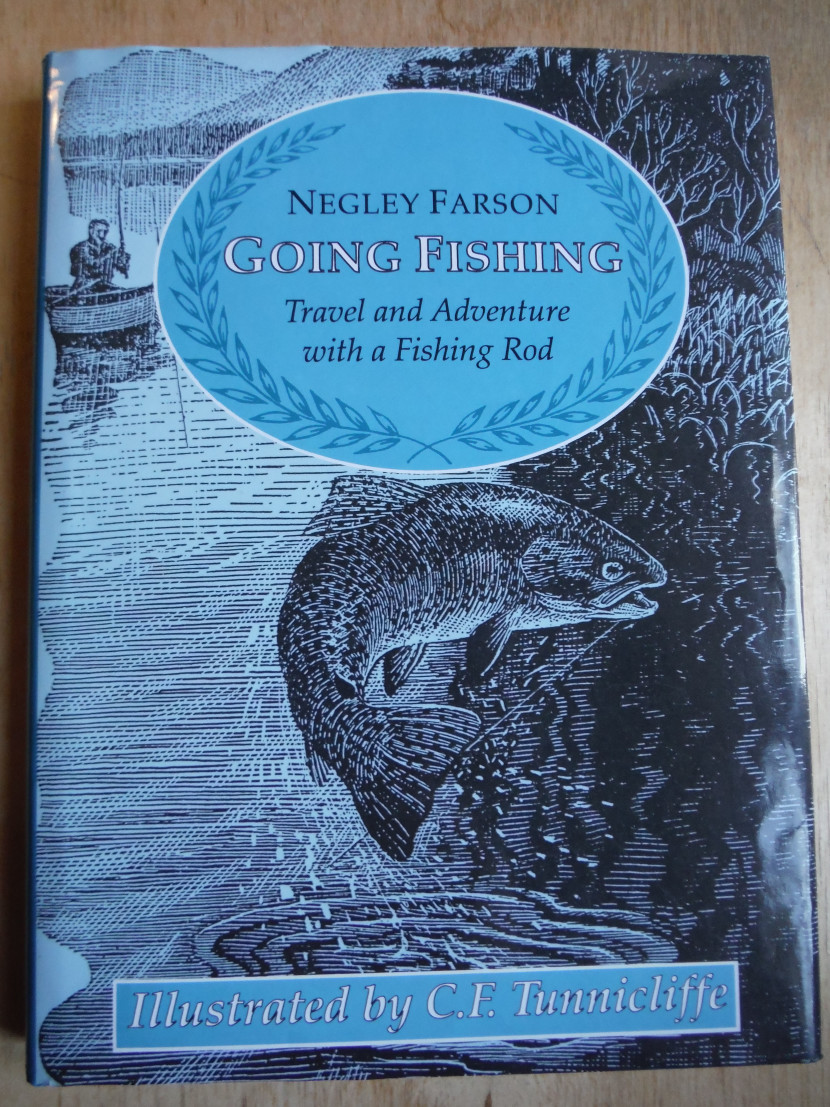

The second writer was from almost a generation earlier and a very different kind of man, although equally adventurous. As far as I know Leigh Fermor didn’t fish, or if so, perhaps very occasionally in the sea for mild amusement. You won’t find much about it in his travel books, wonderful as they are. Negley Farson fished during every moment a busy life allowed him and he fished everywhere. His autobiography, The Way of a Transgressor, used to be a best seller during the 1930s. Despite a certain amount of wandering of my own, I usually tried to squirrel my books away in storage somewhere, probably on the assumption, correct as it turned out, that what I had read for the first time at 25 years old would look different when I returned to it at 65. I have mislaid my copy of that one (it may be under a pile of other books somewhere in the loft), but I remember its story well. I do have to hand the later book he wrote about his fishing, logically enough entitled Going Fishing. This was first published in 1942, but is still in print (White Lion Press) and available from Coch y Bonddu Books. Going Fishing tells the same story, but rather than from the point of view of the adventurer, the arms trader, the truck salesman, the newspaperman and the writer, it is the angler here who looks back on a turbulent life, a life always soothed by fishing and about which, you imagine, he regretted very little.

As an aside, it’s interesting also to compare Negley Farson with his fellow American Ernest Hemingway. We don’t know, but surely they must have bumped into each other while engaged on journalistic assignments between the wars? Both were exceptional writers, and also tough and persuasive men, determined to find the truth behind the events of the day. They both drank heavily. And yet while Hemingway eventually revealed a great deal about himself in his novels, Farson’s equally direct and accurate writing is more guarded about his own affairs. You have the feeling he was the more self-confident of the two. Hemingway was a notorious womaniser; Farson, by all accounts, enjoyed a long and faithful marriage. Hemingway eventually died by his own hand, while Farson seems to have achieved peace in his retirement among English trout streams. Truly, sometime soon I ought to go searching in the loft for that autobiography and read it again, because you need to put the professional career together with the fishing to understand much about Farson, even though the personal life will remain largely private.

Negley Farson was born in 1890 and brought up in New Jersey and then Pennsylvania by his grandfather General James Negley, a Civil War veteran. Most of his youth was seemingly spent in fishing, shooting and sailing in Chesapeake Bay; Going Fishing begins with accounts of wild-fowling and beach fishing for striper bass. After being expelled from school, he studied engineering at Pennsylvania University and then somehow wangled a position representing an American arms dealer to Czarist Russia. This turned out to be an important connection once war started. He eventually spent five years in St Petersburg, and there witnessed the Kerensky Revolution in spring 1917. Later he described a period evacuated to the far shore of the Gulf of Finland, listening to the gunfire around the Kronstadt naval base on the Russian side, while fishing for perch with other exiles from boats in the brackish sea and wondering whether unfriendly Finns in the forests behind would attack them. Later still he claimed to be a Canadian in order to join the British Royal Flying Corps, crashed an Avro while learning to fly in Egypt and sustained leg injuries which laid him up till after the war. He married his English nurse Eve, a niece of Bram Stoker of Dracula fame, and the pair of them eventually went to live on a house boat on a remote lake in British Columbia.

Going Fishing by Negley Farson

Going Fishing by Negley Farson So far in his life, Negley Farson had managed plenty of adventures, but had written hardly at all. Now the plan of the young couple was to live from the products of Negley’s rod and gun while he tried to sell a few short stories. This part of Going Fishing interests a lot of people who secretly nurse romantic dreams of living off the land. However, the book makes it clear that, even in the western wilderness of a century ago, that was a pretty unrealistic ambition, whatever River Cottage addicts might imagine. Unpeopled as the surrounding Great North Woods were, Farson quickly risked falling foul of close seasons and restrictions on shooting and trapping. Nor were his short stories successful at first, at least until he learned to write down his own ideas in his own style, rather than trying to imitate the likes of Somerset Maugham. Nevertheless, the two years in British Columbia form a large part of the book, including descriptions of the salmon run, the hatcheries and the Native American tribes who lived from the salmon.

What happened next is typical Farson: a complete change of lifestyle. Tiring of the good life on the lake, he took his wife to Chicago, where he managed to wangle another influential job, this time as Sales Manager for the Mack Truck Company. In the post-war boom period before the Great Depression, he was quite successful in this role. By 1924 he was apparently bored again, so they left for England, bought a 26 foot Norfolk Broads yawl, The Flame, and spent the next 8 months in trying to sail her from the North Sea to the Black Sea across Europe, up the Rhine from Rotterdam and down the Danube. They had adventures enough; in those days the interconnecting Ludwig Canal across South Germany between the two great rivers, always short of water, was almost completely disused. Farson had to man-haul The Flame through thick weed beds for miles until the Danube was reached. Once Belgrade was attained they left their boat for a while and took a trip through Yugoslavia as far as my wife’s home town of Mostar, which Farson described as an ancient city where veiled women passed mysteriously down narrow cobbled lanes. They were shot at by Bulgarian border guards while passing down the Danube’s international channel, fished for sterlets with the Serbian border guards, and shot duck themselves in Romanian swamps. The last stages of the voyage were tinged with panic and the need to reach open sea before winter came and the river froze.

During the journey, Farson had sent despatches to the Chicago Daily News and this led to a permanent position as foreign correspondent. This was the best possible job for Farson and he excelled in it, being on the road almost without ceasing for the next ten years. This was an era when American reporters were regarded as some of the best in the world and Negley Farson was as competitive as any of them. He covered the British General Strike, De Valera and the Irish, the arrest of Ghandi, fighting on India’s North-West Frontier, Polish atrocities against Ukrainians, Norwegian whaling, the British herring fishery, the Basque country, Lake Victoria and Uganda. He spent a lot of time in the USSR and organised a long and dangerous trip by horse-back across the mountains of the Caucasus. He even managed to be there when the FBI shot down designated public enemy John Dillinger in Chicago. If he was tasked with getting an interview, he was pretty sure to run his man to ground, by hook or by crook. He interviewed Primo De Rivera, dictator of Spain, Carlos Ibanez, former dictator of Chile, and Hitler in Germany, who described Farson’s blonde son as “a good Aryan boy.”

Farson as an international must have had one of those impressive passports, stuffed with colourful visa stamps. Wherever he went, he took at least one spinning or fly rod along. In fact the interest in fishing, while perfectly genuine, was often used as a cover. Fishing his way through Ireland back in 1919 he had written an article for the New York Sun about the activities of the IRA – and fooled few of his Irish interlocutors by all accounts, but, being Irish, they tolerated him because he was a fellow angler. He must have become regarded as something of a specialist in the Danube and the Black Sea area, because it was by living with Russian sturgeon fishermen one winter on the delta that he managed to obtain information about the massacre of Tartars in Romanian-controlled Bessarabia. He later wired his report from Constantinople.

Farson admitted that while sleeping in the fishermen’s stove-warmed tents on the frozen Danube marshes he would dream about the sturgeon, those ancient and mysterious fish with their moon eyes, some of them giants 30 feet long, gliding unseen at the bottom of great rivers and seas. Reputedly they live to be over 100 years old. The sturgeon certainly is an almost mythical creature. In Iran, by Caspian shores, I would hear tall stories about sturgeon and caviar, and how fortunes could be made by fishermen. Sturgeon – and there are many species - are Britain’s royal fish, but rarely seen by us these days, although a century ago they would occasionally make their way into our larger rivers. Britain’s record river-caught fish was once the sturgeon of 358 pounds, foul-hooked by salmon angler Alec Allen in the Towy at Nantgaredig during the dry summer of 1933. It was 9 feet 2 inches long and 59 inches in girth, and had to be carried away with a horse and cart. And our record shore-caught fish was once considered to be the sturgeon of 500 pounds, caught in the Severn estuary by lave netters from my home town of Lydney on 1st June 1937. (I wonder exactly how that was done? Did several of the nets-men somehow box the monster in?) During the 19th century sturgeon were occasionally taken in the Wye as far up as Hereford.

Going Fishing is not a particularly technical book and Farson was quick to emphasize that he had no particular skills or methods to impart. He fished with relatively conventional methods and a small range of standard flies and spinning lures. Most of his tackle seems to have grown old with him. He just kept at it, and in places which few other anglers reached. In his youth, surf casting in New Jersey for the big striped channel bass and ling was accomplished with a double-handed greenheart rod and plain centre-pin reel with a check, although the first multipliers were arriving. Inland and further south there was plug fishing for large-mouthed and small-mouthed bass, not forgetting baiting with live frogs. In the Carolinas, the town drunk taught him to fish for cat-fish and he learned about duck-hunting. From this point, the accounts of shore fishing become mixed with stories of living and sailing with his friends in wooden boats of dubious sea worthiness and of the motley characters then engaged in making a living from oyster dredging.

1917 and the perch fishing in the Gulf of Finland was a way of killing time while fighting was still going on in Petrograd across the water. The next boat along turned out to contain the playwright Leonid Andreyev, author of The Red Laugh and The Seven Who Were Hanged. Andreyev was gloomy; he had supported the February Revolution, but now in October he felt he could not support the Bolsheviks. He never left Finland, dying in poverty a few years later. On this day, however, he caught a 2 pound perch.

After the war, in British Columbia, Farson and his English wife were not unduly troubled by neighbours on their house-boat lake. Half a dozen people lived along a 20 mile shore and most of them were eccentric. Farson could fish and shoot to his heart’s content when he wasn’t writing. Using wet flies like Silver Doctor, he caught rainbows, cut-throats and Dolly Vardens along with steelheads and occasional salmon. A whole chapter of Going Fishing is devoted to the five Pacific salmon species and the lives and potlatch ceremonies of the Indians who fished for them.

The focus of the book shifts across the Atlantic. After the Rhine-Danube adventure and influenced, I suppose, by his Anglo-Irish wife, Farson’s base and eventual permanent home was to become Devon and the West Country. You could make a worse choice, I’m thinking. In fact Farson grew to love every kind of British fishing and his description of it all begins to glow with an additional warmth. Wet fly fishing in the Shetlands for brown and sea trout fits into a long and indeed current tradition. One of his trips to Shetland was combined with writing an article on Olsen, the famous Norwegian whale gunner, who shot an 80 tonner for the occasion. Those were certainly different days. There is a lot about salmon fishing in Scotland where Farson, typically enough, usually reckoned he knew at least as much as the gillie about what to do. While Farson liked his fellow man, he didn’t take advice easily, and I suspect that in fishing at least he was often happier on his own. There is fishing in Ireland too and (rather a rarity this) reference to dry fly fishing at Uxbridge with Foreign Office friends. This would have been on the Middlesex Colne where, between the wars, there was at one time excellent trout fishing and a good mayfly hatch. Apart from the Foreign Office, several of the embassies also maintained water there. Heathrow Airport and the expansion of the western suburbs during the fifties brought game fishing on the Colne practically to an end.

The travelling and fishing went on of course. Farson fished under the Andes in Chile, where rainbow trout had been introduced a few years before, and where a volcano erupted a plume of yellow sulphur gas every 10 minutes; he fished for brown trout in Norway, France’s Haute Savoie and the Regent’s Yugoslavia. The trip across the Caucasus in 1929 had been a long one undertaken with the Englishman Alexander Wicksteed, who had come out to the USSR with Quaker Relief during the worst of the famine a few years before, a time in which he had seen cannibalism along the Volga. There being no other option in that high and wild country drained by the Terek and Kuban rivers under Mount Elbruz, the two men made the journey on horseback. Every few days they bought a sheep and roasted it in the open. To describe the people they moved among as Georgians, Cherkessians, Ossetians, Chechens, Tatars, Turkmen, Dagestanis and Cossacks with a sprinkling of Russians would be a great over-simplification. The journey was, frankly, a dangerous thing to do then and might even be today in that landscape populated by different and often warring peoples, tribes and religions. (I have a pet theory of my own about the effect of terrain on the outlook of their human populations. This theory was possibly evolved – I almost hesitate to mention this - in certain Forest of Dean villages, but quite definitely confirmed in mountainous Eastern Bosnian municipalities like Srebrenica, Bratunac, Zvornik, Foca and Visegrad. The theory is simply that people who live on plains are disposed to be relatively open-minded about both neighbours and travelling strangers. But those who live in steep narrow valleys, hemmed in by the hills, have a distinctly quarrelsome tendency to dislike whoever lives in the next valley even more than they dislike strangers. Am I being unduly pessimistic?)

The two men travelled a region which had recently seen massacres and even genocide, but now lay uneasily under the new Soviet rule. The rod in its wooden case was a real nuisance on horseback, particular on narrow tracks between rocks, but Farson took it along and before the trip was over caught quite a collection of little spotted trout from mountain streams. A friendly Don Cossack, who had appreciated the gift of some fried trout, felt the need to warn Farson that unfortunately he had caught them with a fly, which was a “capitalist” method. Only a worm, he argued, was a reliably socialist way of fishing.

The English West Country was always in Farson’s thoughts while he was abroad. He loved so many things about it, including the shooting in wooded Devon valleys and on upland moors. For a sportsman there was something to do in every month of the year. There is a glorious description of Exmoor stag-hunting. He liked to chat to local countrymen in the pubs and tackle shops and was more than ready to accompany a rabbiting man and his ferrets. In fishing, he accepted quite happily the idea that Devon trout tend to come at three to the pound and could delight in a day sorting through his fly box for patterns like Tups Indispensable, Greenwell’s Glory or Pheasant Tail, meanwhile taking time to look around him at the wildlife on the bank where a small stream ran off the moor. He liked to watch birds and note the emergence of flowers. There would be a bottle of beer and cheese sandwiches in his fishing bag. He remarked that he could not afford to fish on a chalk stream, but that was rather a poor excuse and I think his tongue was firmly in his cheek. The fact is that he liked to fish small rain-fed streams and recognised that they were good for him. Once, when abroad, he wrote about dreaming of reaching England and a place in Somerset where two small rivers meet. There was a fishing hotel which he knew very well and where the locals would gather and chat in the tap-room. And there he knew he would find his peace at last.

Farson wrote Going Fishing from Devon in 1942, and eventually died there after the happiest of retirements, in 1970. His son Daniel, the “good Aryan boy”, became a respected television journalist. Negley Farson finished his last chapter Fishing the West Country of England: Reward, with the hope that neither war nor anything “as evil as progress” would ever change a place like Devon. I suppose the second war did not change it so much, but we can debate the extent to which whatever counts for “progress” has affected the West Country and other parts of Britain. Thanks to specialist travel agents and outfitters, young anglers in normal times today have the world of exotic destinations to choose from, assuming they are able to finance the trip, and I suppose they rarely need to pack a rifle along with the fishing rods. However, I wonder if any among them will gain the joy out of angling which Negley Farson had throughout his adventurous life?

Well, there it is….I still have the old Landrover by the way.

Tight lines,

Oliver Burch