I was in quite a cheerful mood when I signed off the October newsletter. It didn’t last very long. At the time we had something going on in Wales called a “circuit breaker,” a sort of mini-lockdown, but the WUF had helped me to transfer tickets and clients to English rivers, apparently to resolve the problem. Never mind if it was raining; it usually does at this time of year surely. However, it kept on raining and the rivers kept on rising until it dawned on me that there would be no grayling fishing anywhere for at least a week. And then, telling us that he has to do it with a heavy heart, here comes Boris and the scientists (at least the SAGE ones) to tell us we have to lock down in England again. That was a dark moment on a dark afternoon. Personally I can’t blame the poor man; he’s damned if he does and damned if he doesn’t, blamed by most people for everything in fact!

The first priority was to know whether we could go fishing in England this time round. For once there was some good news. Apparently common sense prevails after the previous lockdown experience; it has been acknowledged that a disease whose average victim is 82 years old or otherwise already quite unwell is not spreading particularly fast in the open air. So it is now recognised that for the majority of us, those who are not particularly vulnerable, some time spent fishing or wandering alone in the open countryside is not an unwise or unhealthy thing to do – rather the opposite in fact. When the details emerged, the main restriction seemed to be that anglers should meet no more than one member of another household. In my case, that meant I could guide one angler, but probably not two even if they live together. I’m sure we can put up with that. Less clear was the instruction that we should try not to drive too far for our recreation. How far is too far? Nobody seemed to know, but I guessed an individual policeman would be expected to know on the day. “Don’t go exploring new fishing hundreds of miles away,” is the best advice I have heard. We should also avoid designated high infection areas.

So much for England; Welsh anglers at the same time were still forbidden to drive to their fishing at all. That ruling seemed remarkably unhelpful to the extent of being pointless. Meanwhile, as the population of different parts of the UK struggled to keep up with the latest risk assessments and restrictions on accustomed freedoms, Sweden announced its very first lockdown measure to counteract the virus. Here it is: no more than 8 Swedish persons are to be seated together at a restaurant table, apparently. Some rose tinted memories of jolly parties at a favourite fish restaurant in Uppsala crossed my mind. A painful sacrifice for the Swedish dining public of course, but no doubt necessary. We told my Bosnian/Swedish brother-in-law and his wife how our hearts are bleeding for them.

Although some high pressure weather arrived from the Atlantic, there was still a very long wait for water levels to fall and for game fishing to restart. I saw few grayling reports but temperatures remained high and barbel anglers with 6oz leads were still catching from flood waters in Herefordshire. One grayling angler who managed to buck the trend and do very well in these conditions was JD of Bromyard who somehow managed 13 grayling from the Lugg at Dayhouse on the 7th. The level on the Byton gauge was then at 1ft 9 inches, which I would have described as impossibly high.

Lugg at Dayhouse

Lugg at Dayhouse  Border otter

Border otter Rather than kick my heels at home, I went fishing for rainbow trout in our Forest Pool. We have a rather strange batch of fish in the water at the moment. Although stocked many weeks ago, they are still very much shoaled up. Rather than cruise a regular beat, as most rainbows are accustomed to do, they just hang just below the surface with its freight of dead leaves, apparently motionless. There have been no particular signs of fry feeding and, despite the warm weather, rises to the surface have ceased. In fact they look like weak or sick fish, except that if you drop a fly amongst them they will react, and one at least will have it. So rather than the usual autumn tactics, fishing the pool has been a matter of locating the dark shapes of the shoaled fish, dropping a fly amongst them and striking when a mouth was seen to open and close. Once a fish was hooked, the performance was as lively as normal and after you had caught 2 or 3 the shoal would move away. I used a small Humungus lure fished on a very slow intermediate line, but I dare say any weighted fly would have sufficed.

Otherwise I found that levels in the little Forest of Dean streams had dropped enough to allow for the annual maintenance trim, and I got Blackpool and Bideford Brooks done first, and later Cannop. As yet another demonstration of just how warm the weather was, while pruning the Cannop Brook on the 20th I managed to disturb a nest of wild bees on the bank. They were still very much active and they didn’t like me at all. Before I could make my escape a number had stung me on the left cheek and around the eye. I was shooting the next day and as a left hander the experience of making shots with a burning cheek on the stock and a swollen left eye to peer down the rib on top of the barrel was not so easy. Trimming small streams is a perennial subject of course, but for now I would emphasize that it is all much easier if you make a visit every year, in which case it rarely takes much longer than fishing up the same stretch of water. Another few mornings were spent on the Ross AA water of the Lower Wye, hacking back bank growth and opening up some access for next season’s salmon fishing.

High water at Ross on Wye

High water at Ross on Wye By now my brow was constantly being creased as I stared at maps of the border. On Monday 9th the Welsh circuit breaker came to an end and there were new directions to follow, for Welsh anglers at least. See if you can follow the logic of this situation. On Sunday 8th, English anglers could drive (but not too far) to fish in English streams. Welsh anglers could fish in Welsh streams, but only if they could walk or cycle to the water. They must not drive there. On Monday 9th, English anglers could still fish in English streams (without driving too far), but Welsh anglers could now drive anywhere they liked within the principality to fish Welsh streams. However, no crossing the border in either direction. Which was a pity, because by now some of the Welsh tributaries such as the Irfon had reached a fishable level as the floods receded – but English anglers could not fish there! Where to take my clients? Tourism within Wales is apparently now being encouraged, but not for English visitors. Does this make much sense in terms of fighting the pandemic? I had quite a benign view of devolution to national governments when it was originally introduced many years ago, but I’m starting to revise my opinion when confronted with this sort of nonsense. Maybe, just maybe, some matters are best decided from Westminster for the United Kingdom as a whole and I’m not sure my Welsh friends would disagree.

.jpg?w=830) Court of Noke in the mist

Court of Noke in the mist  Fishing the Lugg

Fishing the Lugg It was raining again. A few people tried to get out despite the restrictions, but, mainly due to the high water levels, there was not much to report. With clients I persevered with some nymphing on the Herefordshire streams, but water levels rising once more made it really difficult. There was still fly life remaining on the water: willow flies with their uncertain flight, pale watery duns and spinners. Gradually, though, the levels went up to an impossible height as rain continued. We may have lost some reports due to a problem with the WUF website in the middle of the month (caused by heavy traffic visiting the water gauges we were told), but in any case nearly all our rivers were now in full flood. No news to speak of was coming from Wales until the 23rd, when MH of Llandrindod Wells with a companion started on the trotting at the GPAIAC water, Builth Wells. They reported 15 grayling and 35 chub, along with a slightly disturbing 20 out of season trout. On the 28th AG from Cardiff reported 8 grayling from Cefnllysgwynne with the trotting rod.

Meanwhile I spent some more time with clients, many of them new to fly fishing, on commercial rainbow fisheries such as Big Well near Monmouth. As a sign of how warm the November weather remained, most of the days being still in double figure temperatures, we caught our fish on dry flies, firstly my favourite Chocolate Drop and then Andrew Herd’s Pheasant Popper, which excelled itself. This is a wonderful little thing when fished round in a wind, kept buoyant and visible by a wing post of yellow foam. Given any kind of ripple, rainbows couldn’t seem to resist it provided it was moving slowly. Here is the recipe if you want to try it:

Hook: Longshank size 14 dry

Silk: Black or brown

Head: Short length of yellow booby cord (Veniards small)

Tail: Natural pheasant tail fibres

Body: as above

Thorax: Brown dubbing

Rib: Fine gold wire

Hackle: Soft henny brown cock

Pheasant Popper

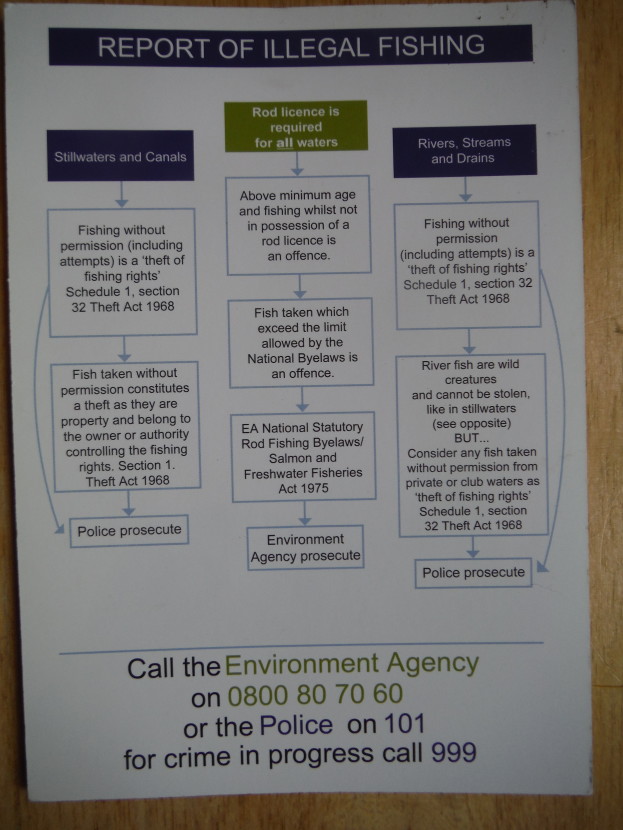

Pheasant Popper  Reporting Poaching

Reporting Poaching The perennial problem of poaching, which should concern all legitimate anglers, has been particularly bad this year. Above right is a photograph of a useful little card somebody gave me the other day. The diagram tells you, in the case of illegal activity spotted on the river, who is responsible, who to call and who will prosecute. Note that in the case of poaching/theft of fishing rights, it is the police who must be informed first, and that it is the police who have the primary responsibility to act.

As a diversion this month, here is an article aimed at both petrol heads and fly fishers. I once claimed to be both at the same time and I still know a few who might qualify by combining those interests. In fact writing now in 2020 I admit to feeling slightly defensive about the following piece, on the basis that a Jeremy Clarkson type of enthusiasm for fast engines has become quite politically incorrect, particularly for those who claim to have an interest in the environment and the countryside. The best defence I can come up with is that for my own motoring these days I’m quite proud to own, apart from my smoky old Landrover, an unglamorous but very economic modern car which averages over 70 mpg. Why the former interest in speed then? In an attempt at illustration, I can only compare myself to the famous socialist who liked Ferraris. (Believe me, I know a thing or two about socialists and their tastes; the sons of several Labour cabinet ministers were in my class at school). While this particular socialist would never be able to afford a Ferrari, never aspired to own one, and in fact couldn’t even justify the existence of a luxury car market while there was poverty remaining in the world, nevertheless he just loved the idea that Ferraris exist and that clever engineers in Italy are able to spend their time designing, building and even racing them. You could have similar feelings about very finely made shot-guns or even fishing reels. Read on if this applies to you, because all will eventually become clear. But if you are one who longs for the day when all internal combustion engines are extinct and only want to read about vehicles powered by batteries, you may wish to skip what follows.

The story is that 50 years ago I used to visit a quiet suburban street of what we used to call “between the wars” houses in a small Hampshire town. The particular red brick house I was making for looked like all the others except that an unusually large garage, perhaps big enough for half a dozen cars, stood in the garden beside it. A knock on the garage door on any day between Tuesday and Saturday (but certainly never on a Monday for reasons which will become apparent) would be answered by a slight middle-aged man, usually dressed in a brown engineering coat and always with a smile. He would usher me into a space packed with all kinds of machinery: lathes, milling machines, bench drills and hydraulic presses. There were benches, vices, tool boxes, welding equipment, grinders, polishers and other devices whose purpose was unclear to me. Leaning together in a corner were the 250cc and 350cc New Imperial motorcycles on which, in his younger days, the owner of this emporium had won races at tracks like Brooklands. However, the main purpose and focus of the whole workshop would be lined up on a central bench, each of them with labels attached and held safely upright bolted to a working cradle constructed of angle iron. These were single cylinder Norton racing engines, the famous twin overhead camshaft “Manx” engines in 350cc and 500cc format. Occasionally there might be a single camshaft “International” engine sent in by somebody who liked to ride very fast on the road.

Ray Petty was what we used to call an engine tuner and in the case of Norton engines his credentials were impeccable. Always fascinated by motorcycles, during the war years Ray had worked at Vickers Aviation assembling experimental aero engines as an assistant to the famous racing tuner Francis Beart. After the war, both of them moved to the Norton factory racing department and were intimately involved with the development of some of the most famous racing motorcycles of all time, the long-established overhead camshaft Nortons twinned with the newly developed “featherbed” frames which had cornering capabilities which still outclass many modern bikes. When Norton withdrew from factory team racing, both men became independent tuners and sponsored riders of their own. Ray, who rode himself in all the Isle of Man TT races from 1948 to 1954, sponsored the legendary Derek Minter for many years. Ray had also experimented in numerous directions, producing a 250cc version of the famous Manx, versions for scrambling, a “back to front” Manx with the carburettor in front, and Norton engines fitted into 500cc Formula 3 cars. Later he built his own frames, improving on the already superb featherbed standard, and also five and six speed gearboxes to improve on the standard Norton four-speeder. In 1966 his engines won 43 races and when I knew him one of his machines had just won the 1971 British title, the last one ever to be taken by a single cylinder machine.

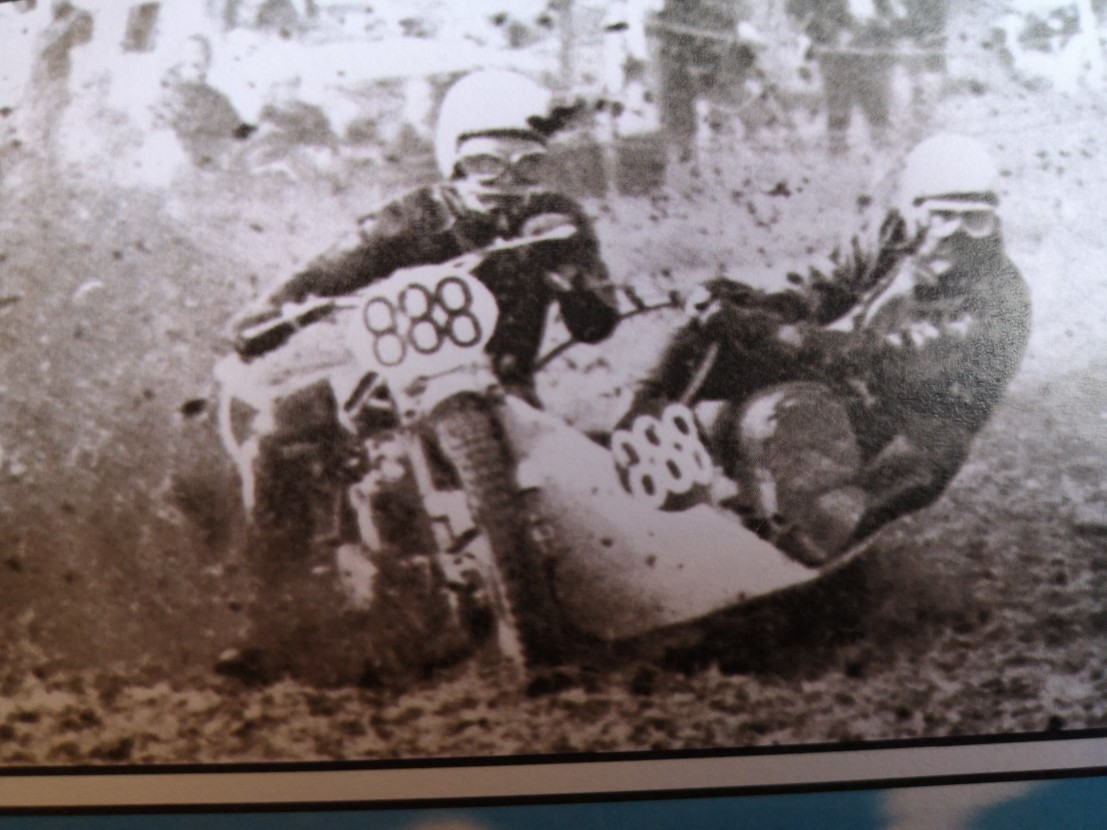

John and I disturbing the peace in Kent

John and I disturbing the peace in Kent By the early 70s, the period I am writing about, British motorcycle racing in the first rank had changed forever with Yamaha two strokes dominating in the 250cc class. Foreign machines of all types had come to the fore and some quite exotic multi-cylinder factory racers from the likes of Honda and MV Augusta had been wowing the crowds (including me on occasions) at Grand Prix races. The late sixties were the years of star riders like Mike Hailwood (who had started on Nortons) and the Italian Giacomo Agostini. At the same time club racing was still dominated by the big British singles, including Matchless and AJS, and in this field a Petty-tuned Norton was more than competitive. Today a Petty Norton occasionally comes up in one of the classic motorcycle auctions and invariably fetches a very high price.

I admit to having had a big interest in the motorcycle road racing scene in those days, but as a young man with a new mortgage, purpose-built club road racers from Norton or Matchless were far beyond my means. Still, the idea of competition was very attractive and my fishing pal John and I had begun to watch the local grass track racing version of the sport. This looked fun and it was definitely much cheaper. We also managed to persuade our new wives that it was safer. So it was that one chilly spring evening, John and I climbed onto my push-rod Norton and rode it down to East Kent. There in somebody’s back shed I put down 150 quid on a grass track sidecar outfit based around a tuned 650cc Triumph engine running on alcohol. The deal we had already made between ourselves was that, as I was putting the money down, I would be the owner and pilot. John would be the passenger but as he was also a very committed and successful coarse competition fisherman, I would need to find somebody else when he had a big match on. Otherwise I would do the mechanics and bear the main costs, but we would share the cost of each meeting. The ride back from Kent on the old Norton ES2 proved very cold indeed and John was far from comfortable on a less than adequate pillion seat. As a result, we kept stopping at pubs to warm up and drink a glass of rum. I can only confess that a cavalier attitude to drinking and driving was shamefully common at the time.

A racing sidecar, even a low sitter rather than a kneeler, is emphatically not a motorcycle with a sidecar bolted as an addition to its left-hand side. It is a purpose-built frame of tubes involving suspension and three wheels, one of which steers and one of which drives, and all of it supporting a platform to climb around on. Our particular version of the sport was known as left-hand or anti-clockwise sidecars, and involved racing the oval in an anti-clockwise direction with the sidecar wheel on the inside of the turn. The driver moves around a certain extent and it is essential that the passenger has his weight over the back wheel to give maximum grip on the start and the straights, but he must be well out over the sidecar wheel to prevent the machine overturning on the bends.

We enjoyed ourselves that first year, but we were never in the money, except for a couple of times in handicap races. The realisation dawned on us soon that we were down on power. In those days there was quite a mixture of engines being used in the sport. Of the solo machines, the 250 cc class power units were taken from unit construction BSA C15s, while the 350cc and 500cc bikes used JAP speedway engines built during the late 1940s. Almost anything went for sidecars, although Triumph parallel twins were more common than anything else. I remember racing against an outfit using an 1100 cc JAP V twin engine from about 1930, another with a 998 cc Vincent V twin and a chap who had pressed an 850 cc three cylinder two stroke from a Saab 99 car into service. The last was memorable for the terrifying shriek it made. Somebody even managed to mate a 1300 cc Volkswagen car engine, an air-cooled flat four, driving by chain to a Norton gear-box in an outfit so long and so heavy that it would charge down the straights but it just would not go round corners. The safety ropes were only just able to stop it and it is a wonder to me that it never managed to kill any spectators. But John and I realised quite quickly that the serious contenders, the real stars of the sport, were all using hybrid engines made by fitting a Norton Dominator crankshaft into the cases of a Triumph twin. This required a bit of machining to achieve, but produced about 830 cc and lots of usable torque. The downside was that if you over-revved them even momentarily it was very easy to break a connecting rod.

The off-season was time for a lot of thought and then some work. I was no engine tuner or machinist, but I did have a small workshop and knew how to tear down and rebuild motorcycles and most engines. How to get more power? We didn’t like the unreliable Norton crankshaft idea, not having the money to keep several spare engines on hand ready for blow-ups and disasters. In the end I decided to invest in a new Triumph engine conversion kit recently designed by the cylinder head specialist Harry Weslake. This was completely revised from the Triumph hemispherical head and twin valve approach, using instead a flat head and four valves per cylinder. Combined with the original crankshaft, now toughened by a nitriding process, Weslake’s head and barrels with light-weight slipper pistons and full race Triumph cams, this gave us a very strong engine measuring about 700 cc. Then, with it all still in pieces, I went to see Ray Petty at his workshop in Cove.

Racing Weslake engines were as new to Ray as they were to me, but he was not at all fazed by the challenge of making mine more efficient still. With the parts on a bench, he looked the proposition over quietly for a while and suggested a trial assembly. Our main aim, as he saw it, would be to achieve a higher compression ratio as we would be running on alcohol rather than petrol. Also, again due to the use of alcohol, we needed to ensure a faster supply of fuel into the engine than usual (alcohol mixes with air at a much richer ratio than petrol). The solutions he eventually came up with were quite simple. Working in stages, he machined off the top of the cylinder barrel to raise the pistons closer to the head. In between machining there were trial assemblies to make sure of adequate clearance between valves and pistons. At the same time, the push rods had to be shortened to match the reduced cylinder height. From what I saw, Ray would use engineer’s blue and ordinary plasticine at times as well as dial test indicators and micrometers when taking his measurements. In this way, the compression ratio was raised from a standard 11:1 to around 14:1, still with adequate clearances. His solution for the fuel supply was first to persuade me to drop the remote tank combined with an electric pump from an E-type Jaguar car which I had been using. That system certainly had varied the delivery from fuel starvation to flooding at different times. Instead, we went back to an ordinary gravity feed through three large-bore pipes. Then Ray cut a horizontal slot inside the float chamber of each Amal carburetter, so that fuel could flood in at high speed as soon as the needle valve raised from its seat. The rest of the work went according to some fairly well-known formulae. One and three quarter inch diameter exhaust pipes exactly 37 inches long were fabricated to fit the outfit’s frame and sprayed matt black. A BTH racing magneto with fixed advance was timed at 35 degrees before top dead centre. I had thought that, with dial test indicator and a 360 degree protractor, I had made a pretty good job of timing the E3134 camshafts. Ray was very diplomatic about it, but he wanted to do it again himself and I had the sense to let him go ahead. His charges were always very reasonable.

All this involved a few visits to Ray’s workshop in Cove through the winter and eventually into the spring. Inevitably we chatted a good deal and of course I wanted to ask about his career at Bracebridge Street under racing manager Joe Craig and his subsequent work with Nortons. I was as fascinated as everybody else with the legendary overhead camshaft Nortons, although I never aspired to own one. Ray told me the story of the Coates Internationals. I was once granted a ride on a Model 30 International, the pre-war road-going precursor to the racing machines. Having a rigid rear end it was a hard ride, but with its single overhead camshaft engine it was surprisingly fast. During the war, Norton had mainly been confined to supplying the army with side valve sloggers painted in camouflage colours for routine military use. But according to Ray, four Internationals were supplied by special request to the Coldstream Guards in 1940. These were for escort and traffic control use by the Coates Mission, the special unit tasked in the event of a German invasion with evacuating the British royal family, including the present Queen and Princess Margaret. Rolls Royce armoured cars were to be used, first taking the family from London to safe houses in the Midlands, and if necessary on to Liverpool. From there they would be taken by sea to Canada. Thankfully the contingency was never needed, but I imagine the convoy would have been escorted at a brisk pace!

The essential reasoning for Ray’s independent tuning work now was that the standard 500cc Manx racing engine as supplied by the factory through the fifties and sixties produced about 45 bhp. This might seem modest compared to modern motorcycles, but in a good frame with the right gearing on the right track it could reach 125 mph. It was generally accepted that Ray could get 50 bhp and maybe a little more. His engines could be run up to 7,500 rpm in the intermediate gears and pulled 8,000 rpm in top if geared correctly. They were known for their reliability. Ray was a wonderful engineer but I don’t think that as a tuner he was concealing any magic modifications to the engines he worked on. He told me, truthfully I believe, that it was mainly a matter of careful attention to ignition and valve timing. His hand-built frames, based on the standard Norton featherbeds but much lighter, were acknowledged to be superb.

While Ray was more than patient with my interest and enthusiasm, it became apparent that there was a subject other than motorcycles which we had in common and one in fact which he wanted to discuss much more. He did a lot of his business on Saturdays, as you might imagine, and so could always be found in his workshop then. On Sunday he was usually at circuits such as Thruxton or Brands Hatch watching one or other of his machines compete. But there was no chance of finding Ray on a Monday, which was a sacred day as far as he as concerned. The reason was that he was a dedicated fly fisherman. On Mondays he had a rod at Alex Behrendt’s Two Lakes, where he regularly fished with the likes of Dick Walker and John Goddard. In those days there was much more cross-over between still water and river fishing. Two Lakes was something of a mecca for fly fishers at that time and I found that Ray had encountered most of the great names of post-war trout fishing, including CF Walker and Terry Thomas. He had also known and fished with Oliver Kite.

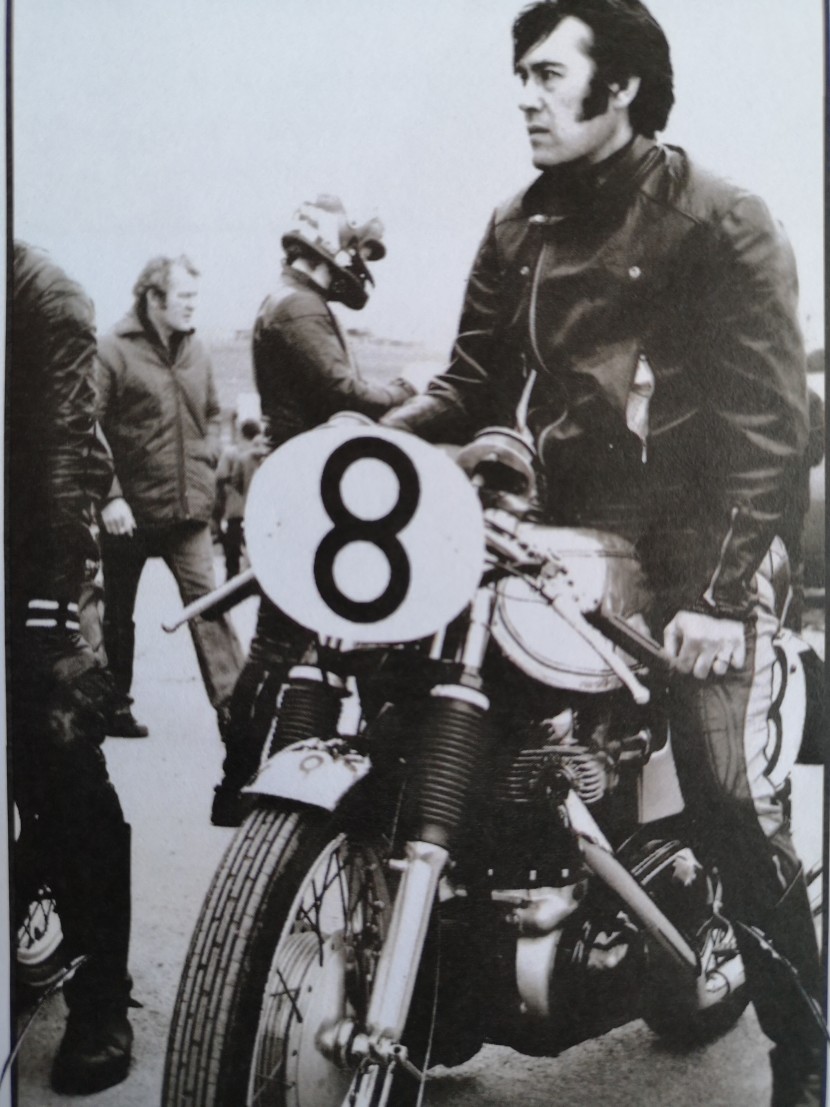

Track day - John and a Norton Dominator

Track day - John and a Norton Dominator John and I were then as keen on fishing as we were on motorcycles, although John was mainly a coarse fisherman and in fact a great all-rounder. Fly fishing for him was something to do during the spring closed season until 16th June. I loved to fly-fish, but in coarse fishing I took on the role of John’s loyal but not very astute apprentice. He taught me what little I know about winter chub fishing with bread flake, trotting for dace, early morning tench fishing on Surrey ponds, night fishing for carp, and appropriate methods for pike, perch and bream. We went fishing for estuary mullet in Devon and for wrasse off Cornish rocks. Apart from trips to the nearby upper Wey where we were as likely to catch dace as trout, most of the fly fishing John and I did by that time involved reservoirs and boats. The Queen Mother Reservoir at Datchet was then a regular resort of ours, although not the prettiest place I have ever fished. This was a concrete bowl where you regularly smelled the jet fuel from exhausts as aircraft dropped low overhead towards Heathrow. To tell the truth, quite a lot of this reservoir fishing involved big rods, lures and some very heavy fast sinking lines. We had to do it on the cheap (by which I mean that we couldn’t afford an engine and I had to row everywhere). We had acquired some kit for the boat, including an anchor made from 60 feet of nylon rope, a length of chain and an old iron cylinder head from a Triumph motorcycle. For controlling drift we had made a rudder which could be clamped in position on the stern, and also a leeboard to clamp to the gunwale to produce a “crabbing across the wind” form of drift. These devices were very popular at the time, but I am not sure they were really so valuable. In a strong wind the leeboard in particular would produce an alarming warping of the whole side of the fibre glass boat. Unsurprisingly, most fishery managements ban their use today. I also had the bright idea of improvising a drogue using a golfing umbrella purloined from an aunt. Opened up and towed behind the boat on a rope this slowed us down beautifully for a while…until a sudden gust of wind collapsed the umbrella’s frame and we accelerated forward.

While much of our early season time was spent at anchor fishing deep, maybe with something like an Ace of Spades lure, more subtle fishing was not completely unknown to us. At Weirwood in Sussex we fished in the bays with floating lines and teams of buzzers, or on summer evenings with dry sedge patterns. Believe it or not, we often used a Red Tag, and later in 1978 I can remember making a killing on that pattern one evening in the newly opened Bewl Reservoir’s Dunster Bay. We had come to realise by then that any fish which shows on the surface could be caught on a dry fly, along with some of those which didn’t. In that sense we were quite advanced, because very few anglers used the dry fly on reservoirs in those days.

Ray, on the other hand, was not much interested in fishing from boats. His still water trout angling was all done from the bank with floating lines, nymphs and very long leaders. He was absolutely fascinated by very sensitive takes from nervous trout and he had a lot to say about bite detection and leader make-up. I gathered his great hero then was the nymph-fisher Arthur Cove. John and I probably looked more to Bob Church at the same time. However, I could quite understand Ray Petty’s philosophy of angling. It seemed to me that a man who spent his working days calculating tolerances to less than a thousandth of an inch would naturally espouse some very subtle methods in his fishing. I do remember discussing with Ray the Deer Hair Nymph method. The idea was that on a size 10 or 12 hook you made a ball-shaped and buoyant fly of ordinary trimmed deer hair, rather like the “biscuit flies” used to catch carp nowadays. You fished this from the bank on a floating line and 20 foot leader, with a split shot pinched on the leader, usually about 12 inches from the fly. This was cast out “down the slope,” allowed to rest for a while with the split shot on the bottom and the nymph anchored just above, then very slowly inched in until the split shot moved and the nymph dipped and jogged sideways, then left still again for a couple of minute, and so on. A full retrieve might take 15 minutes. Provided conditions were still, concentration on the half-sunk tip of the line told you everything you needed to know about what was going on down below. The use of split shot is rather frowned upon nowadays in this country, but I remember the method as very effective for bottom feeding trout, especially browns.

John in later years, still fishing

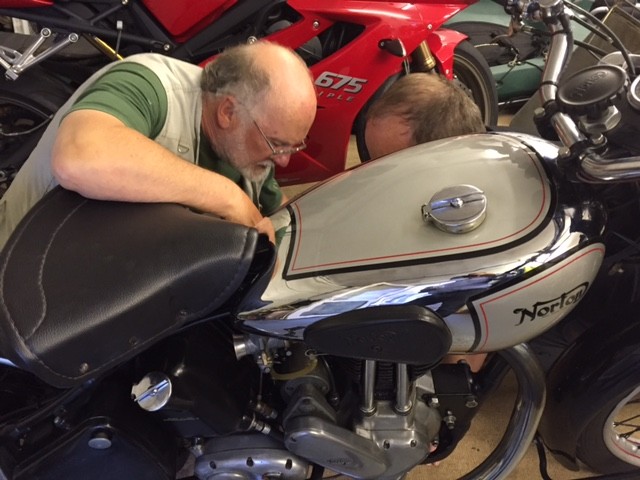

John in later years, still fishing  Lyn's ES2

Lyn's ES2 And how did John and I get on with our newly fettled Petty-Weslake side-car racer? Well, it certainly was powerful. The engine was never tested on a dynamometer, but Ray reckoned that, given the high compression ratio and the alcohol fuel, we might have about 80 bhp. To tell the truth, I found it quite frightening. We now had enough power to show up all the handling deficiencies in the chassis as well as my own deficiencies in riding skills. Moreover, the engine was producing its main power like a road-racer at high revs rather than delivering mid-range torque. As a result, it was very difficult in slippery conditions to “feel” for grip with the back wheel. In grass track ideally you should transfer power to the ground with about 25 percent slippage all the way round the course, but not more. On dry days with lots of grip we did rather well and got as good a speed on the straights as anybody else. But in the rain we struggled, with the engine shrieking and the back wheel constantly spinning free on slick mud. In those circumstance, one of the big V twins with good low speed torque and grip could easily get past us.

Still we had fun and we competed for a couple more seasons. Now and then John would miss a race meeting for a fishing match and I would have to inveigle and cajole some other unfortunate friend to borrow his leathers and be my passenger for the day. I admit to having taken a slightly sadistic pleasure in this, because most of them would find the experience terrifying and there was no practice opportunity prior to the racing day. Once the outfit was out on the track, there was no chance for the guest to jump off, but instead the urgent need to hang on for dear life! Nobody got hurt, but I don’t recall anybody asking to do it twice. Eventually, family responsibilities including children, not to mention fishing and even work, took up our time and we retired. In the end I sold the engine to a chap who wanted to use it in motorcycle drag racing at Santa Pod.

Ray Petty died in 1987 but his legacy of beautiful racing machines lives on in motor-cycling circles. People remember him for what he achieved in the sport, many without knowing much about him as a man. I will remember him as a craftsman and as a gentleman, with much patience for a young enthusiast. John, my former passenger and one of the nicest blokes I ever knew, a good husband and family man, died a couple of years ago. Our later lives went in different directions, but we kept in touch now and then. He always had a motorcycle or two around at home and occasionally an exotic car such as a Ford Mustang. He fished all his life, latterly with a grandchild. For myself, I haven’t been near a racing motorcycle for a long time. Accidents involving friends and fast motorcycles on the road turned me against bikes altogether for a while. The boy next door was killed in a road accident while the daughter of a friend was badly smashed up while despatch riding in London. By the time I had growing sons, I didn’t want them to get a taste for two wheeled excitement.

However, a few years ago my fishing pal Lyn Davies, already the owner of a rather glamorous Triumph Daytona track bike, mentioned to me that it would be nice to have in his garage an old-fashioned British single cylinder machine, maybe something from the 1950s. This was a relatively unknown field to Lyn, who is quite a bit younger than me. He wasn’t interested in speed this time and just wanted something for the road with character and a cooking engine. “What about a Norton ES2?” I suggested, remembering my lovable old thumper which I used to take on fishing trips. This was a reliable, slow-revving design with a big fly wheel. “Advance the ignition, engage top gear and let it go bang every second lamp-post” we used to say. And in fact Lyn managed to buy exactly the bike I had owned and ridden down to Kent with John fifty years before, same year and same model, a 1950 push rod ES2 with garden gate frame, road-holder forks and plunger rear suspension. The glaring difference was that I had paid 45 pounds for mine in 1969 and he paid 4,500 pounds for his. So much for inflation! I must admit that his example is in nicer condition than mine was.

Lyn's ES2 push rod engine

Lyn's ES2 push rod engine  Wallace and Grommet - me, Lyn, and Lyn's Norton ES2

Wallace and Grommet - me, Lyn, and Lyn's Norton ES2 Towards the end of November we had high pressure for a change with an associated cold, dry snap and a conversation with Seth at the WUF revealed some very good news for once. As the floods gradually dropped away during a period of cold night frosts, it became apparent that a lot of salmon had taken advantage of the high water to get well up into the tributaries and that the low temperatures had already triggered the spawning activity and red cutting. Inside a few days WUF staff recorded spawning salmon well up the main river, in the Edw, Sgithwen, the Irfon as far up as Abergwesyn, and in very good numbers in the Arrow and Lugg. While out with a guest I spotted a cock fish in the Arrow at The Leen; many more were seen in the Pembridge area and 9 redds were spotted in the Lugg at Lyepole. Only the Monnow system remained stubbornly without evidence of spawning access, and for that we can probably blame the formidable barrier on the lower river at Osbaston, just above Monmouth. Osbaston Weir and its turbines have long been recognised as a major problem for fish migration.

Autumn morning at Lyepole

Autumn morning at Lyepole  Abbeydore

Abbeydore This was good news indeed after a lack-lustre salmon fishing season, but at once we found ourselves presented with quite a serious dilemma. This year of all years, due to the virus we have very little to offer English anglers during the winter except grayling fishing on the Herefordshire streams. Given reasonable water conditions, we would expect fisheries like Lyepole, Dayhouse, Eyton, The Leen and Court of Noke to be quite busy this winter with anglers fishing the new close nymphing methods. But with the gravel beds of the Lugg and Arrow now housing fresh-laid salmon eggs – remember, no less than 10 new redds seen at Lyepole this week – should we be encouraging or even allowing anglers to wade through the pools while fishing heavy nymphs along the bottom? Would it not make more sense to fish these beats from the bank with the trotting rod?

High water on the Arrow

High water on the Arrow  Dore grayling

Dore grayling  Dore pools

Dore pools I make no bones about the fact that I like to trot a bait for grayling during the winter. I like it because it is a very delicate and effective method, and a traditional one too, for what that is worth. It could also just be that I am reaching the age when a winter day spent on the bank or near it is slightly more comfortable than one spent waist-deep in the river. So far, I have taken the view that I prefer to trot at long range on the big pools and runs of the main Wye, many parts of which cannot be easily reached into with the fly rod. I also have some favourite places on the Irfon which are much too deep to be reached when wading, but where a float trotted down from above can be highly effective. To date I have been less convinced about smaller streams such as the Lugg and Arrow – currently only The Leen, Court of Noke and Manor Farm offer trotting as an option – but any significant risk of damaging salmon redds is certainly enough to change my view. Maybe trotting from the bank would be a more responsible approach? The WUF is going to contact owners on these streams to see what they think about the trotting option. With some reluctance, for the moment I am going to stay away from wading them with the fly rod. That was going to be my winter treat, but I think it’s a good principle that we give spawning fish every chance, just as we should move away to a new swim if catching too many of an out of season species. Seth and I would be interested to know what you think about this subject.

To be honest, at this stage I’m not clear what English anglers are going to be able to do next month if there are still objections to crossing the border. Welsh grayling anglers should have a good choice of the upper Wye, Irfon and Ithon if water levels will permit. For the English I might point out that there are three beats of the Dore open for grayling. This is a stream unlikely to be affected much by salmon spawning and safely within Herefordshire. Don’t all rush, have as good a Christmas as you can manage and tight lines!

Oliver Burch

Last of the leaves

Last of the leaves