As we turned into the new month the weather was dry and cold, resulting in a short period when the rivers were at a level to make grayling catches possible. On 29th November PT from Kidderminster caught 19 grayling from the Eyton beat of the Lugg with trotting gear. Our old friend AG from Harleston, Norfolk, fished Ty Newydd on the Wye with nymphs and accounted for 6 grayling. On 1st December DW from Gloucester caught 3 grayling trotting the Lugg at Lyepole; on the following day at the same beat he caught 16 more. This happy fishing period didn’t last long as very heavy rain on the 4th sent levels up again and more rain kept them up for the rest of December. There even snow in the North, but our part of the Border Marches was spared that particular pleasure. I had to delay a number of scheduled days with clients as the floods continued to race down the Wye while the skies became ever windier and wetter. I consoled myself with some mornings shooting at clays launched with rather erratic and wavering paths into the air currents of the storm. Some shooters complain but I rather enjoy wobbling targets. I also fished our Forest Pool with a Black Lure in order to catch some rainbows, although even there the water had thickened with mud from the inlet streams.

Lugg at Lyepole

Lugg at Lyepole  Winter rainbow

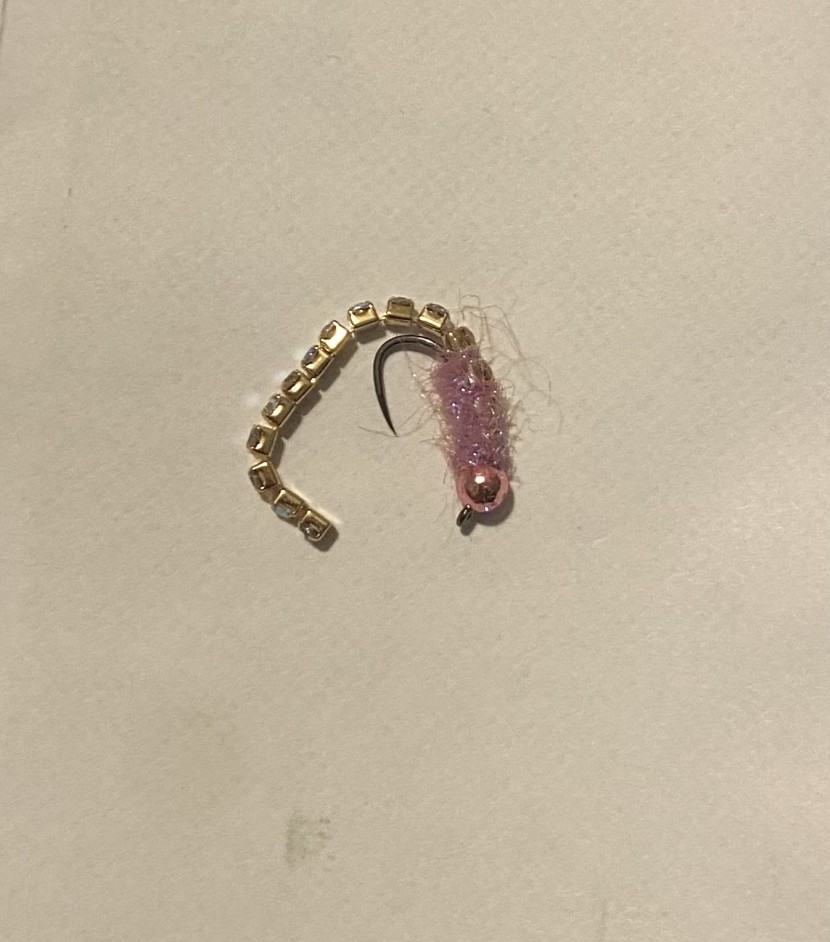

Winter rainbow  Jewelled grayling fly

Jewelled grayling fly On the 9th IS from Gloucester caught 2 chub and 14 barbel from the middle Wye at How Capel Court. On the 11th DM from Camberley managed a barbel and 3 chub from Middle Hill Court, really a heroic achievement as the level was now up by over 3 metres. IS from Gloucester was back at How Caple Court on the 12th and this time managed a remarkable catch: 2 barbel, both in double figures, and 17 chub up to 6.5 pounds.

Chub were the fish of my boyhood and now I wonder how our younger selves would have reacted to the reality of a 6 pounds chub. A 2.5 pound chub from the Thames tributaries we fished then seemed big. If you delve into the history of British record fish, you quickly find your way back to what might have been creatures of legend and mythology. The once supposed chub record, the 10 pounder claimed during the 19th century from the River Crane in Middlesex, by that time seemed like an impossible legend. It could hardly be verified by us as it came from a place already buried beneath the runways of Heathrow.

While most of us were flooded off the Wye system, Lyn Davies and Rob Evans headed up to the Hanak Grayling Festival at Llangollen. Here they found the Dee at a more reasonable height and with plenty of fish, although with the famous competition in progress numerous anglers were scratching to catch them during the practice sessions. “Hard work fishing,” said Lyn who mentioned he saw quite a few spawning salmon while in the Dee. Over his two match sessions he ended up with 18 grayling in all sizes to 17 inches. Lyn brought back news of a magic Irish nymph, made with a tail of fine bead chain and pictured here. Apparently it sinks like a stone and English and Welsh grayling cannot resist it, even if its Irish originators have no grayling to practice on. He had to buy a lot of Guinness to find out about this. Incidentally, Lyn’s production unit (that’s his girlfriend Sara) has completed a second video about fishing the upper Irfon, this time at Melyn Cildu back in October:

By the 17th the Wye level had dropped a little, such as to allow MH from Llandrindod Wells to catch 13 grayling trotting on the GPAIAC water at Builth Wells. AB from London managed 6 grayling to 40cm from the top of the Irfon at Melyn Cildu. Almost immediately more rain brought the rivers up again, so that fishing had to stop while air temperatures were now strangely and unseasonably warm. Just getting to a shooting ground near Upton on Severn became an exercise in map reading because the big river was creeping out of its bed and over the fields. Little interconnected lakes were forming all the way to the Malvern Hills; locals in the Severn Valley get quite used to this semi-aquatic life style. I spent the morning of Storm Pia fishing our Forest Pool while the trees tossed in the gale, keeping a weather eye out for branches cracking overhead. I found myself muttering lines from that wonderful description of an autumn storm: On Wenlock Edge the wood’s in trouble…thick on Severn snow the leaves – but even Housman would have been taken aback by the strength of this wind. Douglas Firs lose their side branches regularly; they crack suddenly off the trunk and fall point down like a dart to drive into the ground and they can weigh more than a quarter ton. At such times, under the tree is no place to be standing. I was using a floating line with a slightly weighted Damsel Nymph and the rainbow fishing was wonderful, hooked fish leaping again and again from the highly oxygenated water and ripping lines out to the backing knot. However, I opted for safety and retired after lunch. Forest roads were blocked and I got home to find a section of the garden fence down.

Cefnllysgwynne - Lyn Davies

Cefnllysgwynne - Lyn Davies There isn’t much to report from the holiday period, the rivers having being so high and with hardly any respite in the rain. Lyn Davies fished the Irfon at Cefnllysgwynne on the 17th for a couple of grayling shots along with out of season trout. “More goosander than grayling,” was his verdict on the day. On the 20th MK from Bristol fishing for barbel at Middle Hill Court had a nasty experience in the floods. A sudden wrap-around bite had him grabbing for the rod as it shot off the rest, but he slipped in the mud and slid down the bank. The tackle was lost and so was the angler very nearly, according to his account. Rather gamely he went into Ross to buy replacement tackle, pressed on with fishing at Middle Hill Court and ended the day with a barbel and several chub.

By Christmas week and with the warm rains continuing, the rivers grew ever higher. The Wye burst its banks and flooded the fields between Hereford and Ross. The inundated valley of the Severn above Gloucester now seemed to have widened by several miles. For some reason during Storm Gerrit I drove down to our port where a wind from the end of the world was rolling the yachts side to side on their moorings. Once outside the rocking car, I was soaked in seconds, tasting salt on the wind. I should have known it would be strong; facing up to a south westerly pushing a full tide into the Bristol Channel feels much as I imagine a passage around the Horn on a windjammer would be. I walked just as far as Naas Manor, an old Severn-side house which has been battered by storms ever since it was first fortified and then bombarded in the Civil War. You can see it has had a hard life.

Flood fishing at How Caple Court - CM from Keynsham

Flood fishing at How Caple Court - CM from Keynsham  Naas Manor

Naas Manor In between floods, I did find time to finish the pruning on my local Wild Streams, the Bideford, Blackpool and Cannop Brooks. Nobody should imagine this means that there will be no obstructions left to get in the way of conventional overhead casts the visiting angler cares to make anywhere on the water. I deliberately leave vegetation in place wherever possible, which means that branches will be left hanging low over shallow stickles which will not normally hold fish and that nothing will be cut which is more than about 5 feet above the surface. Given that I visit only annually with the cutting gear, I don’t bother with brambles or vines which will grow again within 3 or 3 weeks, and as I don’t have power tools, fallen trees will necessarily be left in place. There must be a dozen newly fallen trees down over the Cannop Brook this year and there they will stay until Forestry England carries out another tree thinning exercise and sends timber extraction machinery into the wood. Woody debris in the water is usually deliberately left in place because small fish like it. To summarise, Wild Streams are in their nature just as the title describes: some of the water can’t be fished, yet there will be there will be plenty more left to go at, and there will be a good deal more side and roll-casting possible than conventional overhead casting. The opportunity for an overhead cast on these streams counts as a rare treat.

Bideford Brook in winter

Bideford Brook in winter  Blackpool Brook - high canopy

Blackpool Brook - high canopy  Cannop Brook after trimming

Cannop Brook after trimming The other day a researcher from Forestry England called me up to ask my opinion “as a representative of the angling community” on the reintroduction of pine martens into the Dean. It’s always nice to be asked. To be honest, after some reflection, I couldn’t find an opinion within myself. I had not even been aware that the little fellows were back (apparently there are 35 of them here) and I certainly haven’t seen one. I supposed that people particularly concerned about song bird populations might object, as a nest full of fledglings makes an ideal meal for a marten. Or further north, in forests where there is still a red squirrel population, martens might be unwelcome. They have a reputation for being able to kill young lambs. I do have an opinion about the reintroduction of beavers after an absence of 400 years: I think it’s a mistake. The story about beavers in the Forest of Dean is that a pair were introduced in an enclosed area above Lydbrook during Michael Gove’s time as Environment Secretary, with the idea that they would create a series of dams on a steep gradient and thus hold back water from flooding the village. The first pair died of disease, but they have been replaced and this year the new pair had kits. Another beaver introduction is now due to take place on the headwaters of the Blackpool Brook, in flat marshy forest near Speech House.

The January edition of Trout and Salmon carries an interesting if slightly confusing article about a giant salmon caught on the lower Usk as long ago as 1782. There is little doubt that the great fish was real, although unfortunately it was not taken by rod and line but caught in a net between two coracles manned by Richard Reece and James Lewis near Llantrisant. By all accounts the capture was much celebrated and the fish was taken around the district to be shown. We can place the capture on the modern Llangiby fishery, or perhaps on the Crown Waters, just a few miles below Usk town. A first draft of several paintings made at the time has now been found in the store rooms of Abergavenny Museum, but it is unfortunately in a poor condition and due for restoration. At the request of Jean Williams, formerly of Sweets Tackle, the Usk Rural Life Museum and the Usk Fisheries Association, some dark and stained varnish is being removed and a new frame fitted. Fred Buller in The Domesday Book of Giant Salmon featured this fish and provided a photograph of one of the later paintings of it, this one found in Derby, and apparently now residing in Devon after fetching 5,000 pounds at auction. Although it was not taken on rod and line – more commercial coracle and nets-men than anglers would have been fishing in 1782 – it is relatively well documented and a fine example of a great fish from the period when the Usk also produced giants.

Llantrisant salmon

Llantrisant salmon The slight problem comes with the exact weight. Dr Guy Mawle has pointed out Fred Buller’s contention that the weight was given originally in Dutch pounds (apparently quite commonly used in those days) rather than English. If we convert to metric, it could be assumed that Buller was using 494.09 grams for a Dutch pound compared to 453.59 for British avoirdupois. Therefore if we go by the avoirdupois measure, this fish would actually have weighed 74.5 pounds. However, I’m thinking the matter may not be quite so simple and the Usk fish may or may not be a rival to several giant Severn fish and one found dead in the Wye. If Wikipedia is to be trusted, the Dutch, great trading nation that they are, used a variety of local measurements before they gradually adopted metric systems early in the 19th century. If the Amsterdam pound was being used, 494.09 grams would be correct and we have a 74 pounder here. That would make it the biggest salmon taken by any means from the Bristol Channel rivers and probably the biggest ever taken in England and Wales. However, if the Gorinchem pound (466 grams) was used, the fish’s weight reduces considerably. Then again, if it was the Utrecht heavy pound (497.8 grams) the Usk fish becomes even bigger still. I can well understand the English tendency to adopt Dutch measures while their fishing boats were still selling lasts and crans of herring in our ports. But it also strikes me that in 1782, we were actually at war with the Netherlands, so the weighing of our fine fish by Dutch measures then is additionally intriguing! Now the inscription on the painting shows a weight of 68.5 pounds, yet Buller in The Domesday Book of Giant Salmon (no 363) awarded it only 62.75 pounds. Buller, it seems, opted for the more modest of several possibilities and used a conversion rate of 1.0892 from British avoirdupois to pounds Dutch.

Are you as confused as I am? Any ideas about this? Answers on a postcard please…Whether the true weight was above or below 70 pounds, Reece and Lewis caught a wonderful salmon and the restored picture is due to be on display in Abergavenny Museum from February 2024 as the centre piece of a display entitled “Big Fish.”

Small ponds fascinate small boys, at least they did me. When I was a child living in Surrey, there were many such pools to explore, an adventure initially undertaken by bicycle. Some were mill ponds on tributary brooks of the Wey or Mole, built to reserve a head of water, but redundant by the post-war years like the mills they once drove, now gradually silting and becoming clogged up with reeds. Roach and rudd might be there. Most of the village greens had dew ponds, originally made with puddled clay to water grazing animals, but now a place for ducks to swim. They might contain tench and in one case I can recall little gold money minted Crucian carp which liked to shelter under an overhanging willow. And the estate lakes were everywhere in and amongst the woods and parks, originally built on some wealthy owner’s whim to improve the landscape. These pools often had common and mirror carp, a species of monster which then filled me with awe. I was broken a few times before I ever caught one. It was remarkable in those far-off days how easily, if you asked politely, fishing permission was granted to short-trousered boys armed with bamboo fishing poles and bright red quill floats. Did people have more time for children back in the fifties and sixties? There were times, I must confess, when fearing a rejection we didn’t ask for permission. It was always good to be up and about early.

Reed mace

Reed mace There was – in fact there still is – one particular estate lake which gave me many happy memories. We used to call it Hatchlands Lake, although its correct name is the Sheepwash Pool, and it lies in the park of a great house under the northern slope of the chalk downs near the village of East Clandon. The shallow pond was made by running a low concrete wall along the edge of the estate by an oak wood. A quiet and easily overlooked lane leads you down to it from the village. (Was it BB who wrote that all the best carp waters can be found at the bottom of overgrown lanes?) Ancient iron railings adorn the top of the concrete dam, which closed off a corner of the park and must have originally flooded a couple of acres. Although the pond was named “sheepwash” we were told the family from the House used it as a swimming pool early in the 20th century and you could see the wooden stumps of what might have been a diving board still projecting from the surface. When I first knew it, though, the pond had an abandoned look, severely silted while beds of reed mace were encroaching from either end. On the Park side of the water you had grassland scattered with majestic chestnut trees browsed to a sharp line underneath by the cows. From the entrance to the Park with a cattle grid there was a view of a white carriage road running up a slope to Hatchlands House in the distance. The House and Park had recently been the home of the Goodhart-Rendel family who later made it over to the National Trust. Closer at hand in the Park was Home Farm, from where a flock of noisy geese would issue daily out of the yard to muddy up the pond. In those days, if you gave the farmer 5 shillings, you had permission to fish the pond. The price from the farm went up to a pound over the years, but later still I was very grateful to get a free pass from the National Trust manager as a “local angler”.

John and I were certainly not the first to fish the pool in Hatchlands Park. The angling writer Maurice Wiggin had rented Tea Cosy Cottage in East Clandon during the 1950s and local people remembered him pottering around the village on a single cylinder Matchless motorcycle. As most of the villagers including Wiggin and his wife were tenants of the Estate, he was right to describe this time as the end of an era of private ownership and his landlord, the eccentric and slightly querulous architect Goodhart-Rendel of whom Wiggin was secretly rather fond, as the “last Squire of East Clandon.” After the Estate was broken up, everything had changed.

Wiggin fished the pond regularly in summer and I was told he would deliberately drive the farm geese into it to stir up the mud and the fish before commencing. When we got to know the water, we realised how intelligent this approach was. You have to appreciate just how very muddy this lake was at that time. I may exaggerate, but I had the impression that most of it consisted of 18 inches of water overlaying about a yard depth of fine silt with the boundary between the two materials being indeterminate. Accordingly you could not fish with any kind of leger or indeed anything of weight which would immediately sink out of reach into the soft mud. You had to rely on the innate weight of the slowly sinking bait itself to cast it out. The water was absolutely opaque; you could not see through an inch of it. And in this kind of soup lived what I imagine were millions of very small gudgeon, perfectly pale in colour due to the murk, and within seconds all over any bait you dropped in. There were also vast numbers of stunted roach, equally pale and generally unwanted by ambitious fishers such as we considered ourselves to be.

The real masters of the pond were the wild carp, which rooted and rolled around in the muck like pigs. They were quite visible when they broke the surface. Occasionally one would jump showing grey/bronze flanks and orange fins. Or you would see stems of reed lean apart from each other as a carp pushed his way through the bed below the surface. The distance between the tilting stems would be an indication of the thickness of the fish behind the head and a general cause for excitement. The carp were very fond of the beds of giant reed mace and with reason; these jungles were safe refuge for them and they would stay close. Very occasionally we would come across a “mudding” fish, usually against the dam where it would be rooting in the bottom and stirring up even thicker mud in clouds. This tended to happen at dawn or dusk and we had already learned to avoid the hot part of the day. What we found then is that if you sneaked up on such a mudding fish and dropped in a size 6 hook embedded in a large piece of bread flake squeezed to hold water so that it would sink slowly, assuming the gudgeon didn’t find and destroy it, sooner or later you would get a run from the carp. Even then the Hatchlands fish were shy enough to panic and run when they picked up a bait with their protrusive lips and they were quick to eject. Sometimes, however, the fish would be hooked and all hell would break lose. Unfortunately all I had at the time was a 6 foot solid fibre glass rod and a little fixed spool reel: an outfit definitely not up to the job of subduing the first rush of a wild carp. Inevitably the rod would buckle over into a hoop, the reel would shriek and the fish would be in the reed bed before you knew what had happened. There would be movement for a couple of seconds and then all would go rigid. If you pulled hard enough, you usually got back the hook straightened out. I remember that one time I amazed a teenaged friend by thrusting the rod into his hand and plunging off the dam and into the reed bed myself in a desperate effort to free a weeded fish. The excursion into the swamp ended in total failure and I looked like the character on the Forrest Gump muddy T-shirt until I got home for a bath.

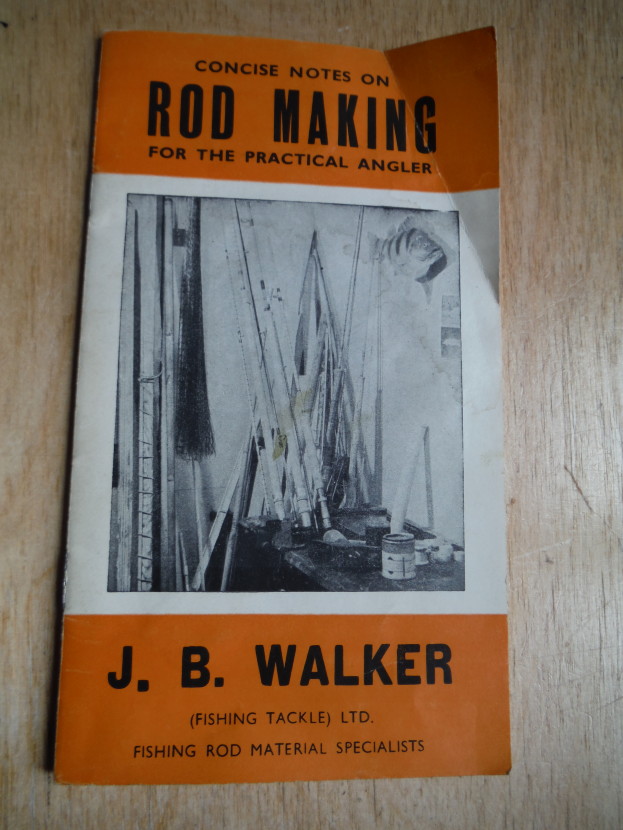

Walker's rod kits

Walker's rod kits Time passed, we obtained motorcycles, cars and occasionally girl-friends, but still we fished the old pond, extracting carp successfully now and then. By this time I had some more appropriate tackle. I had built myself a 10 foot Mk 4 carp rod using split cane blanks from JB Walker of Hythe which arrived with a little book of instructions for gluing corks and whipping on rings and ferrules. This was truly a lovely rod, designed by our hero Dick Walker, and it was twinned with a Mitchel 300 reel loaded with 8 pounds BS nylon. Along with some big strong hooks, a big net, some rod rests and a loaf of bread, this seemed to be all that was needed. For bait you wanted a factory loaf of soft, white and glutinous sliced bread, the sort you probably wouldn’t want to eat. Mother’s Pride was ideal. We still fished early mornings, but occasionally on weekends we would go through the night. The technique at dawn, if the air was still, was to cast a large piece of bread flake just off the reed beds, hold the rod and strike as soon as the line was seen moving away in the early light.

Fishing by night when the fish moved around more, the idea was to make a cast into the middle of the pond, after which the rod would be laid on rests facing the bait and with the bail arm of the reel open. Then a short length of nylon would be pulled off the spool and a crinkly piece of silver paper from a cigarette or sweet packet loosely squeezed over it. That would be dropped into a strategic position on the ground next to my canvas camp chair and I would settle down to wait, perchance to dream. The edge of the wood by Hatchlands Lake in the middle of the night was an eerie kind of place, the long hours punctuated by sudden screeches from owls or foxes or the scream of a murdered rabbit. Rats would be troublesome on warmer nights, running along the top of the concrete dam and over your feet, or trying to pull the bread bait from the paper bag under your chair. Then, perhaps at one or two in the morning, a different “rustle, rustle” from the cigarette paper in the grass would indicate that a fish was on the bait. Visible only as a little flash in the darkness, as the run started the silver paper would suddenly fly up towards the butt ring, upon which you would turn the reel to close the bail arm and strike up to set the hook. Or not, as the case might be. This might sound quite primitive and perhaps it was, but the panoply of modern carp fishing aids such as bite alarms and bolt rigs along with bivouac tents was yet to arrive. In those days carp netted during the night were put back in the lake inside a communal sack, to be inspected and perhaps photographed before releasing after dawn. Then, tired and damp with dew and with the new sun rising through the trees of the Park, we would climb the overgrown lane to the road where the cars were parked and so home to breakfast.

Hatchlands carp were not so big, but impressively long and muscular as members of the race of wild fish usually are, with shovel-like fins and tails. There were a lot of 4 and 5 pounders, although we were always expecting giants. I remember John caught a 7 pounder one night, which I think was the largest wild fish we encountered. However, not so far down the road was a pool with a different calibre of carp. I believe that Hatchlands, rather than being solely rain-fed, must include a natural spring, because the lake has a permanently dripping overflow which is source for a ditch which then becomes a tiny brook flowing north past Ripley and under the A3, eventually to join the Wey via the Ockham Mill Stream. About a mile south by the railway line to Guildford this brook feeds another and deeper pool surrounded by ancient oak trees and here I once had tantalising glimpses of enormous fish, proper king carp, as they turned over under overhanging branches. One memorable night in Hatchlands John had caught a mirror carp of 9.5 pounds and we were told that this one had been stocked from the other pool. Unfortunately, attractive as this second pool was to us, it was located on the neighbouring sporting estate owned by Sir Charles Forte, and the keeper’s dwelling, Pond Cottage, was right there, overlooking the pool. The keeper was one of the old school and I didn’t give much for our chances of gaining fishing permission. My father and I were once shouted at for merely walking along the far bank having strayed from the footpath and I think the keeper had enough trouble from the depredations of a certain pheasant loving gentleman living in East Clandon to keep him in a bad temper.

I don’t think either John or I had really caught the carp bug at that time, as both of us were also interested in other kinds of fishing including reservoir trout, motor cycle racing, and we even had some obligations at work. Nevertheless as the years went by I would go and fish Hatchlands now and then, a few times every summer. I remember taking both my older sons there as infants, which must place this later period at nearly 50 years ago. There are a few different kinds of fish in the lake. I have caught crucian carp on occasions. Once I came across a large domestic gold fish gliding in clear water behind the reeds right in the far corner and I could only imagine somebody had put it there from a garden pond. Early that same morning I suddenly came face to face with a big dog fox at the bottom end. Probably he had been after rabbits on the Forte estate and he just stood there staring at me as the seconds ticked past. Eventually I waved my hand and he took off. (Such unexpected confrontations with something wild and fine to see have actually proved quite common over the years. It happens with Forest of Dean fallow deer all the time. There were griffon vultures in various locations in Southern Europe and a proud little mouflon with sweeping horns in Cyprus. I once surprised a leopard on a forest track in Sri Lanka and felt no sense of threat; he just stared nervously for a moment and then was away at once).

I recall now the dubious experiment of fishing for eels on a hot August afternoon at Hatchlands, using a dead gudgeon presented over chopped pieces of gudgeon catapulted out as groundbait. I think I had the idea from an article in the angling press. After almost melting in the sun I did catch a large eel which went snaking away with the bait, but it was altogether a messy and smelly business and I did not repeat it. More memorable was some wonderful fishing during one fine October morning on which the first frost nip of autumn had somehow sharpened the appetites of the carp. I was still doing nothing more complicated than free-lining a largish piece of bread flake. Every time I cast out the bait, even before it had sunk there would be a run within seconds. I believe I caught more than 20 of the Hatchlands carp that morning. Later for some reason we got more and more interested in floating crust as a bait. If you fed in some free offerings close to the reed beds, it would be possible to get a number of carp interested in the surface. Much depends on the wind direction, but this has some of the charm of dry fly fishing. However, I’m ashamed to report on an occasion when I must have dozed off to wake up suddenly and find one of the farm geese had grabbed the floating crust. It wasn’t hurt as the hook point had merely caught in a dry corner of the hard beak, but the bird was most unhappy at being played and released. Of course I apologised to him.

Then, while I was absent for several years at some time in the eighties, the Estate carried out a refurbishment of the pond. Much of the silt was dredged out and the reed mace beds drastically cut back. I was surprised to see the changes when I returned, but clearly there would now be a much larger pond to fish. The science of carp fishing had advanced by leaps and bounds in the meantime, but not with me. I still had the old Mk 4 cane rod, the Mitchell 300 reel and a loaf of white bread. I started to fish in the time honoured way and caught a few carp. One thing I noticed immediately and wondered at was that now no small fish were troubling the bait. The gudgeon and undersized roach seemed to have disappeared. I kept feeding bread ground bait into the same place, caught several more wild carp, and then hooked into something which was slower than usual but seemed really heavy. It circled for a while and then the olive brown upper lobe of the tail started to break the surface. There was nothing unusual about that except that the tight line was cutting the water a good yard ahead of the tail! What kind of carp from a pond is 3 feet long I started to think to myself? The answer in this case was no kind of carp. After a couple of minutes a big boot-shaped head broke the surface, and a wide mouth opened giving me a sight of grinning white teeth and red gills. I subsequently netted a very good pike in the high teens of pounds, caught fairly and squarely on a lump of bread flake. This was the only predator I ever caught from Hatchlands and I presumed somebody had put it in to mop up the small fish. It had certainly done a good job.

I think I was in my fifties the last time I fished the Pool. I remember taking my stepson Zlatko there as a 9 year old and his grandmother used to display a photograph of him proudly holding a Hatchlands carp. I think it is on the coffee table of the Mostar flat. Zlatko is a father of four and nearly forty himself now. The Mk 4 cane rod, which eventually caught a 30 pounder in a gravel pit, sadly was stolen somehow over the years. That is the only cane rod I would really still like to own again – and if anybody comes across it, the butt section is signed under the varnish with my name and the date, 1973! According to the internet, the lake is still there and went through another refurbishment in 2018, including dredging again, cutting back the reeds and with some wooden revetments to support the bank. Over the years the cattle in the Park had trampled the edge while drinking at the margins. Much is made now of the different species of dragonflies present. You can see it all today on a walk round the Park organised by the National Trust and Clandon has its own village fishing club, just to fish the Pool.

Wild carp

Wild carp December was the month Oliver Dowden announced to a shocked House of Commons that a “sustained effort to interfere in British politics” had been made by Putin’s FSB organisation, which had breached our digital defences using the code word Centre 18. The aim of the Russian secret service attack had apparently been to spread confusion and malfunction amongst our governing bodies. Well, bless you Mr Putin, you need not have troubled yourself with that! I thought everybody knew that Westminster is perfectly capable of doing that for itself, as it demonstrates regularly.

A good example amongst many of the chaotic way in which we run our country these days is the current inquiry into the Covid response which is costing the tax payer many millions, mostly in fees to some remarkably smug-looking lawyers, and is due to continue for several years more. Instead of trying to find out which decisions worked out well and which worked out badly, and what lessons might be learned for a future health crisis, or even where Covid came from, the inquiry seems mainly interested in trivia, such as who said what in private meetings, the content of private Whatsapp messages, who had nasty things to say about colleagues and was the working atmosphere “toxic.” So we had evidence from medical advisers, irritated that their advice was not always taken without question, complaining now that the politicians they were advising were scientifically illiterate; we had everybody complaining that the PM’s advisor was rude to them, and then we had the PM’s advisor himself criticising everybody else involved for incompetence, including especially his boss the PM, who had first defended and then sacked him. And of course we had Partygate all over again. The slogan “follow the science” becomes meaningless when the scientists don’t agree with each other. My understanding has always been that such emergency task forces consist of specialists who give advice, and elected political leaders who must take the final decisions. And that in a crisis elected leaders have the right to change their mind as often as they wish. The only witness who did not use the inquiry to criticise other members of the Covid team, despite all the slings and arrows aimed at him, was the then PM, Boris Johnson. It wouldn’t be his style, would it?

Rather than waste money on this particularly pointless inquiry, perhaps we would do better to take Sweden’s approach as a model the next time we have to face a pandemic. Sweden has finished with Covid and already completed their inquiry, which determined that the country came through the crisis better than most. Sweden chose not to lock down and did not destroy their economy. Most of their government decisions were recommendations for voluntary actions rather than mandatory on the public. Sweden offered voluntary protection should they want it to the perceived vulnerable section of the population, for example people of my age, while everybody else carried on as usual. A few sports events were cancelled, but schools, shops, factories and workplaces remained open. Food for thought?

Two sea winter salmon, Pwll y Faedda

Two sea winter salmon, Pwll y Faedda  Wye overflowing at Bigsweir

Wye overflowing at Bigsweir  Wye salmon days

Wye salmon days I can’t claim this has been a good year, either for seeking a quiet life in the British countryside or for the wider world. 2023 ended with two bloody wars in full flow and uncomfortably close at hand. Apart from the human misery resulting, either or both of them have the potential to become wider conflicts and both already affect world commodity prices and may do further. Oddly enough, I can feel a slight sense of optimism about each of them, although the protagonists surely do not. If Hamas is defeated in Gaza, it might now be possible to imagine a viable Palestinian state, something which has proved for decades to be beyond reach. 2024 might yield some original and creative thinking after this latest round of misery. The much-vaunted counter-offensive in the Ukraine came to nothing this summer, although friends serving in the British Army still believe that Russia can be definitively defeated by a NATO-backed Ukraine. I always disagreed with Boris about that idea. However, now that we have reached the second winter of the war, the grim reality of the military situation is impressing itself. Meanwhile there are signs that western nations are losing their enthusiasm for supporting a Ukrainian system which people are only now remembering is notorious for its corruption. Peace talks would be better embarked on sooner rather than later. Russia, which hosts more Ukrainian refugees than any other nation, will likely be prepared to come to the negotiating table, but partition will be the result. To express the situation cynically (and misquote Mrs Thatcher), to prosecute a war you must rely on other people’s money, which will run out sooner or later. In the case of Israel, it is the US which will at some point call time. In the case of Ukraine, donor fatigue is already very much in evidence.

A few nice things did happen this Christmas. A favourite moment for me was watching Fairytale of New York performed at Shane Macgowan’s funeral in Nenagh, County Tipperary. Uplifting that was; or if you like, a story of a love affair, migration and Christmas. Another small pleasure, as I’m the one known in this house for fondness for old movies, was sitting down with a glass and watching the western Missouri Breaks with Jack Nicholson, Marlon Brando and Harry Dean Stanton. The film was panned by critics when it came out in 1976 and it barely recovered its production costs, but it is gaining a reputation now and its charm and humour for me lie in Thomas McGuane’s screenplay. McGuane also wrote The Longest Silence, which I still consider to be the best 20th century book on angling in the English language.

Our family gathered again this year, this time in a cottage of St Briavels at the summit of the Forest. (According to ancient Forest Law, to be treated as a true Forester, you have to be born in the Hundred of St Briavels. The lack of a maternity unit in the Hundred puts tradition at a disadvantage these days). We cooked some rather fine dinners, walked in the Forest and played with the grandchildren, but it was generally a quiet time. After it was all over and the family dispersed I was thinking: wouldn’t it be something now if we could have a decent salmon run in the coming year? We can live in hope.

Happy New Year!

Oliver Burch