October was another “incomplete” month. By that I mean that we finished it with fishing in Wales locked down once more due to national efforts against the virus and again we anglers had that sense of missed opportunities. There is some excellent grayling fishing in Herefordshire to be sure, but the main quantity of our autumn fishing is in Wales and so at the time of writing was out of bounds to most of us. Rain and high river levels have hardly helped.

First, here are a couple of reports left from the end of September, when our rivers were still low. KL from Bristol on the 29th had a surprisingly good session on the Forest of Dean’s Blackpool Brook, recording 7 trout from 10-12 inches and 2 roach. Catching a 12 inch trout from that little stream is quite an achievement so I think the fact that (by his own admission) he used a Squirmy Wormy fly should be forgiven. Can we call the Squirmy Wormy a fly or should it be a Garden Fly? Anyway, who am I to judge? At 9 years old and in short trousers and wellies, your own correspondent took his very first trout from the same section of the Blackpool Brook. With my bamboo rod six feet long I had walked down through the Forest from my grandmother’s house on the top of the hill and the fly used on that occasion was also a particularly special one. Let me just repeat the words of Harry Plunket Greene that neither forks nor spades would dig its real name from me. So never mind and well done to KL!

Meanwhile EC from Oxford wasn’t very happy with the nearby Bideford Brook on the same day, mainly because it seemed too busy with the adjoining footpath and also because of the nearby sewage farm which had a smell to it that day and because he could hear the humming of the pumps. I appreciate that the footpath from the village has been unusually busy this year and in fact it’s a favourite walk of mine when not fishing. However, I think I take issue with EC’s implication that anglers should automatically be warned if any beat has proximity to a sewage farm, water treatment works, call them what you will. The fact is that because almost all our valleys contain human settlements, most of them have sewage treatment plants, quite a number of them near WUF beats. Thank God! Can you imagine what it would be like if the treatment plants weren’t there? The Blakeney works does not discharge into the brook. EC caught a trout and a roach on his visit.

Autumn glory on Forest pool

Autumn glory on Forest pool Moving on to larger streams, on the 1st October AB from Bromsgrove had half a dozen grayling from the River Lugg at Lyepole. This point marked a change in the weather and the end of a month-long drought. 2nd October brought storms and heavy rain which continued, off and on, for the following week. Later we heard that the 3rd was the wettest day ever recorded in the UK, which perhaps makes what happened next less surprising. Step by step, our rivers rose and coloured until we faced heavy floods almost everywhere and the grayling and even salmon fishing necessarily halted. On the other hand the barbel fishing of the middle Wye was definitely enhanced and some fine bags were taken. After the drought, a rise of 5 feet or so of muddy water was quite welcomed by barbel anglers who pursue a fish which essentially finds its food by smell. On the 7th CM from Ware with two friends recorded 29 barbel from Middle Hill Court including a fish of 11 pounds 6 ounces.

Meanwhile game fishers were forced from the water; the only exceptions I could find included regular RW from Portishead who on the 6th found the Bideford Brook at a level just about fishable. This is a Severn tributary and so was then still open for trout fishing. RW got 7 of them from 8-10 inches. On the 7th NB from Reading fished the Irfon at Cefnllysgwynne, the river being at what I would have thought was an impossibly high level (above 1 metre on the Cilmery gauge), but he did manage a couple of grayling to 12 inches. Another very impressive barbel catch was made on the 9th by a team of 4 anglers led by SC from Leeds. They fished at the Creel and caught 49 barbel to 11 lbs 4 oz to complete their five day holiday on the Wye. I am wandering away from my game angling remit here, but can I take a moment to point out the value to our local border economy of such trips and such a quality of sport? Long may it continue! By the 11th, when I would have said our rivers were still too high for practical fishing, a couple of grayling anglers nevertheless achieved notable catches. NB from Reading fished the Irfon at Cefnllysgwynne and managed to catch 8 grayling on dry sedge patterns fished in the margins, while KL from Bristol fished very heavy nymphs in thick water on the Dayhouse Lugg and recorded 15 grayling for the day. AG of Harleston made his annual visit from Norfolk and on the 16th had 4 grayling to 16 inches from Doldowlod, followed next day by 18 to 15 inches from Cefnllysgwynne, and finally 3 to an impressive 17 inches from Cildu. I understand that, no doubt due to high water, he was mostly fishing with nymphs.

Not much good for salmon, but barbel anglers are happy - CM from Ware

Not much good for salmon, but barbel anglers are happy - CM from Ware  Fishing a pool tail on the Irfon

Fishing a pool tail on the Irfon  Cammarch Hotel grayling

Cammarch Hotel grayling  Dayhouse Lugg

Dayhouse Lugg Meanwhile a few salmon started to appear in catch returns for both rivers: Roberto Fraga had three in a morning from the Usk at Chainbridge while regular KG of Birmingham had another from the upper Wye at Abernant. Brian Skinner had one of 12 pounds from the top boards at Gromaine. To the surprise of many, the rivers just kept running high, very clear now, but only dropping an inch or even less per day. Apparently with the ground so wet quite minor showers in the hills could send the Wye back up again. In the last week of the season, this resulted in a real bonanza of fly-caught salmon catches from the upper river, the fish having been enabled to run through at last, and in the final days the lower river also came onto form. They weren’t showing much, but they were certainly taking now. A few salmon suddenly became a lot of salmon and as many as 25 a day were being recorded to the rods before we closed. I had the pleasure of netting two of them for clients: a 37 inch hen fish for Francis Rundall from the tail of Ty Mawr at the Rectory, and a cheeky little 3 pounds grilse for Alan Ockenden on Bigsweir. More on the salmon season later.

Autumn colours on the Irfon

Autumn colours on the Irfon  Irfon cock salmon

Irfon cock salmon  Irfon's Glaslyn Pool - All three images taken by PR from Shrewsbury

Irfon's Glaslyn Pool - All three images taken by PR from Shrewsbury On the 18th IC from Gloucestershire had two specimen grayling, 17 and 18 inches, in a catch from the Lugg at Eyton. An 18 inch grayling is a likely 2.5 pounder and certainly one to remember. AG from Harleston was now up in North Wales and he recorded 18 grayling to 15 inches from the Dee at Glyndwr Preserve. The Usk and the main Wye stem were now closed for salmon fishing, but the top of the Wye and tributaries remain open for one week more. In contrast to the beginning of the month, salmon were now showing in a lot of places. PR from Shrewsbury with a friend had an 8 pounds cock fish from the Little Glaslyn Pool at Cefnllysgwynne and lost a hen from the unnamed pool below.

There was a time when such major tributaries and the top of the main river held some fish through the summer when rains had provided running water, but now they only show up at the very back-end of the season. The Irfon’s main Glaslyn pool, Little Glaslyn and the one below (I don’t know its name either) are all capable of holding salmon and grayling also. Rain and more high water were still making the grayling fishing difficult, but GM from Shrewsbury had half a dozen from the Irfon at Gofynne on the 21st. Bands of rain kept coming in from the west and for the most part rivers were now too high for productive grayling fishing although the last days of the month were quite warm.

Court of Noke grayling - AD from Kenilworth2

Court of Noke grayling - AD from Kenilworth2  Abernant in a cold wind

Abernant in a cold wind  Eyton grayling

Eyton grayling What shall we say about the salmon and trout seasons just past? Of course it was an extraordinary year, no doubt about that, and the complete cessation of angling for a large part of it made a huge difference. There is much to be said about why we stopped angling and indeed whether there was ever any need to stop, but that is probably best left to a post-mortem when the epidemic is over. We hardly had any spring trout fishing on the Usk this year, a great loss as far as I was concerned, but the river really fished surprisingly well when the anglers came back later in the summer. Before that the mayfly fishing on Wye tributaries was also quite good. The mayfly coincided with that first unaccustomed period during which we could travel to fish in England, but not to Wales, which resulted in some unusual drives around the border.

Sea trout fishing in Wales, which eventually became available first for locals and then later for visitors, was generally poor for another year. The lack of fish led to much concern among clubs, many of whom have written to Welsh ministers and assembly members applying for increased attention to the state of local rivers and to netting and farming practices. Nobody is holding their breath. I took part in the drafting of a letter asking for a meeting with a Welsh minister and we were more or less brushed off, effectively being told the minister is busy, why not go and have a chat with NRW? More incidents involving poaching and pollution did nothing to improve the mood of Welsh anglers.

Oddly enough, the late salmon run in rivers like the Towy and the Loughor was really quite good and there was a distinct impression by the end of the season that there were more salmon present in Welsh rivers than sewin. The Wye was very different and prolific catches during the last days should not obscure the fact that, for the third time now, we have had a poor season. For the upper beats, there was hardly anything to do until the final couple of weeks.

There is no difficulty in assigning reasons. Firstly a lack of angling effort during the spring lock-down resulted in blank sheets for those middle river beats which, even when numbers are low, normally console themselves with some fine early fish.

Autumn salmon from Abernant - KG of Birmingham

Autumn salmon from Abernant - KG of Birmingham Secondly the algal pollution due to high phosphate levels (the WUF should be congratulated for highlighting this to the general public) must have inhibited the summer fishing. There were times when the water looked like soup and the fly had to be cleaned of muck after every cast. Finally a third summer of extended drought confined most of the fish to below Monmouth until close to the end. Is that just bad luck, or are these the kind of summers we can expect in future? I am more than glad for those anglers who had late fish, but a total catch for the year of around 600, while better than originally expected, is still worrying, particularly after the steadily increasing growth in numbers we had experienced up to 2017. It is always difficult to get accurate figures for the Usk, but the trend seemed to follow that on the Wye. Anyway, in 2021 I will try to find time for salmon fishing, but I will also be hoping for one of those old-fashioned wet British summers which supposedly used to spoil family holidays, but kept the rivers running full.

Harvest salmon for Francis Rundall at the Rectory

Harvest salmon for Francis Rundall at the Rectory  Autumn salmon going back

Autumn salmon going back “The lamps are going out all over Europe; we shall not see them lit again in our time.” The famous and poignant remark which almost everybody knows was made by the 1st Viscount Grey of Falloden, then Foreign Secretary. It was late in the evening of 3rd August 1914, and he was speaking to John Alfred Spender, editor of the Westminster Gazette. The two men were looking from the window of his room at the Foreign Office across St James Park to the first lamps being lit on the Mall. They had concluded that war now looked inevitable. Whenever I used to hear that quotation, my main thought was how unlucky could a man possibly be, to find himself in the role of British Foreign Secretary at the outbreak of the Great War?

Most people don’t know much more about Sir Edward Grey than the famous quotation and what history tells us about his official life in politics. Anglers, however, may be aware that years before the same man wrote a quite wonderful and charming book on our sport, entitled simply and modestly Fly Fishing. Reading it, you have the impression that Edward Grey was essentially a modest man. I also conclude that, like many of the rest of us perhaps, he managed to be simultaneously both a lucky and an unlucky man. Born in 1862 to a substantial inheritance in the North Country, you have the sense of slightly unenthusiastic acquiescence to family expectations as he progressed via Winchester and Balliol to parliament, representing Berwick on Tweed at the age of just 23. The “baby of the house” was a somewhat diffident public speaker and slow to give a maiden speech, but progressed steadily as a Liberal with a specialisation in foreign affairs.

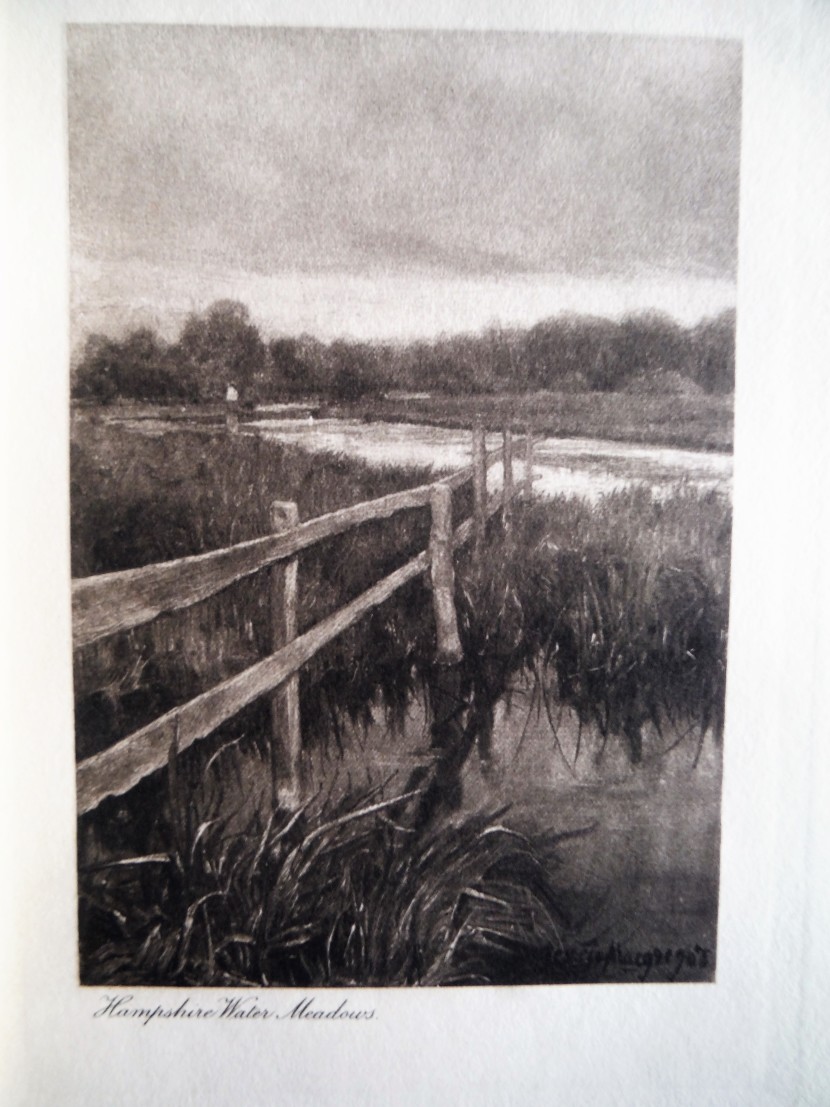

His fishing book was published in 1899 when he was already deeply engaged in the political and administrative world. There is a strong sense of reluctance regarding his political career evident in his writing, and he makes it clear on numerous occasions that any day he would prefer to be on a river or at least in the countryside rather than in his London ministry. Some men would have gloried in political and diplomatic work and the attention and respect which high position brings. Grey saw it all as a matter of duty and a path of duty hard to bear at that. Still he followed it with a sigh, although he certainly could have afforded to step aside. He was perhaps an extreme example of a Victorian affected by that famous Anglo-Saxon work ethic. His book describes the misery of being trapped in London offices during early summer, “…no coolness comes with the summer heat and bedroom windows open into ovens.” This was slightly relieved by receiving envelopes of flowers and plants from his garden at home, posted to the office to please him. “Perhaps you own a distant garden, which you know by heart, and from which occasionally leaves and flowers are sent to you in London; you unpack them and spread them out and look at them, spelling out from them and recalling to memory what the garden is like at this time.” There is also a very detailed description for our benefit about how best to escape from Whitehall to Hampshire, which was obviously his idea of heaven. He expected to work till midnight on Friday (that work ethic again), but come Saturday morning at first light he knew exactly where to find a hansom cab to dash across the river and catch the early train from Waterloo station.

Fly fishing

Fly fishing  Fly fishing by Sir Edward Grey

Fly fishing by Sir Edward Grey  Rural pleasures

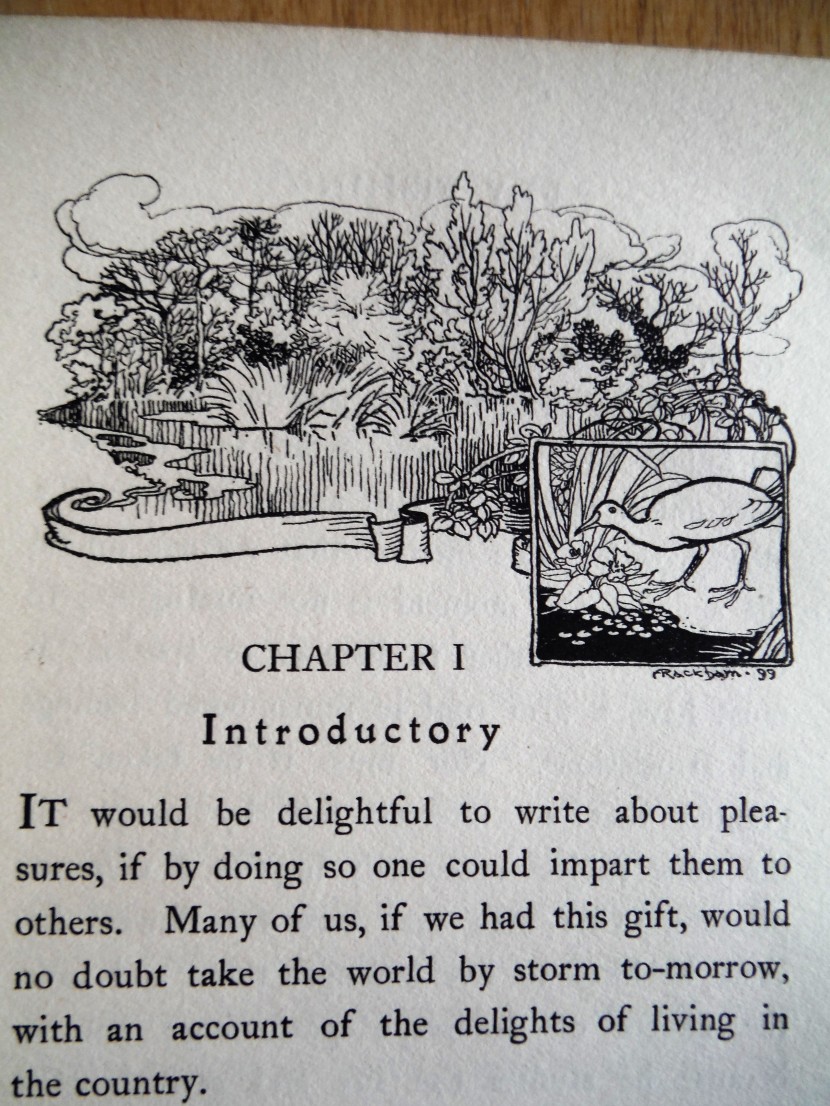

Rural pleasures In Fly Fishing Grey transmits his delight in the natural world and he describes the riverside and the seasons with great detail. Grey is not and will not be the first or last writer to equate trout fishing with the pursuit of happiness However, the book is a lot more than just a joyous celebration of the countryside, because Grey was clearly a very competent angler and he gives much interesting advice. His chapter on dry fly fishing defers to Halford, the accepted authority of the time, but he has plenty of ideas of his own and his description of the changing months on the chalk streams he knew so well is engaging. He also appreciates the significant differences between rain-fed and chalk rivers:

“A true chalk stream has few tributaries. The valleys on the higher ground near it have no streams; the rain falls upon the great expanse of high exposed downs, and sinks silently into the chalk, till somewhere in a large low valley it rises in constant springs, and a full river starts from them towards the sea. There is always something mysterious to me in looking at these rivers, so little affected by the weather of the moment, fed continually by secret springs, flowing with a sort of swiftness, but for the most part (except close to mills and hatches) silently, and with water which looks too pure and clear for that of a river of common life.”

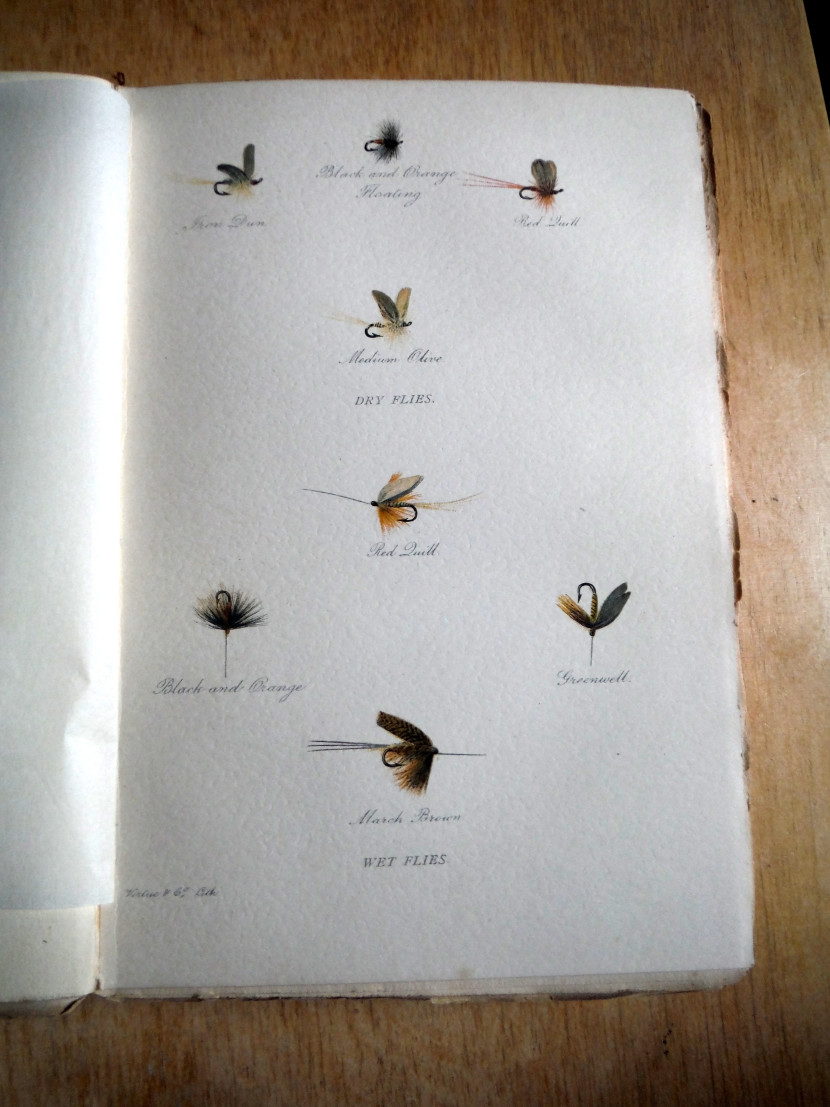

Grey’s favourite chalk stream months were May and June, and as you might expect he waited for the rise rather than fishing the water. But note that in those days, according to Grey, sustained hatches and rises lasting even for 4 hours might be expected. Imagine! He was not a huge fan of the mayfly time, feeling that it spoiled the fishing later in the season. He describes some very difficult fishing during evening rises to small olives, which sounds quite familiar. The iron blue seems to have been more common in his day than it is in ours. Despite the predominance at the time of Halford and his dry fly code, Grey’s writing shows an interest in fishing downstream on occasions, to avoid “showing the fish the gut.” His collection of “regular” dry flies, which are illustrated, was relatively small: Black and Orange Hackle, Red Quill, Iron Blue Dun, Medium Olive, along with a small sedge imitation to be used in the last half hour of light and a mayfly pattern for occasional use.

Haddon Hall edition of sporting books

Haddon Hall edition of sporting books A whole chapter is devoted to learning to fish the Itchen as a boy at Winchester. Now it’s well known that Winchester School permitted pupils to fish (I see it is still on the College’s extensive list of sports) but in those days it was with such restrictive conditions and timings as to make success very difficult indeed. Grey, who first went to the school in 1876, described angling as not taught, though not discouraged. There was about an hour between the end of morning lessons and lunch, and boys would run to and from the river. He began in March with a 13 foot double hander and the team of wet flies he had learned to use at home in the north, and caught very little on a hard-fished public water. Still, Grey persevered and eventually began to catch some Itchen trout from Old Barge and the Millpond, beats which would later become familiar to GEM Skues. He bought his flies from Hammonds in Winchester town. He was also able to observe some “great men” at work on the river: Francis Francis fishing Old Barge with a double hander and Marryat, whom he described as a genius with a fly rod. In his final year at the school he accounted for 76 Itchen trout, mostly with the dry fly.

Fly Fishing is not solely a book about Hampshire, although Grey was primarily a chalk stream fisher. Brought up in the north, he was perfectly familiar with wet fly fishing with spiders and salmon angling too in the Tweed. Describing the prevalence of dry fly and wet fly in different parts of the British Isles he betrays something of Foreign Office attitudes to maps and nations in that late imperial era:

“It is the habit nowadays for nations to divide maps into what they call spheres of influence; a division which sometimes accords with geographical and natural conditions, and at other times is arbitrary. Something of the same kind is possible with the wet fly and the dry fly…Roughly it may be said that the dry fly method possesses the South of England, while the wet fly is superior in the West and North of England and in Scotland. In the midlands and in parts of Yorkshire there is a disputed territory where both are used, and where there may be a real competition between them.”

This was of course written at a time when the dry fly method was still quite a new idea although it certainly had spread rapidly. It’s worth noting that Grey does not champion one method over the other, reasoning that each is best suited to a particular type of river. He was more than happy to use a team of wet flies on the Tweed and the Coquet, fishing them down and across and progressing downstream (although he makes it clear he is well aware of Stewart’s writings on the subject). I wonder whether this habit, perhaps, may have accounted for his missing quite a few takes: “Time after time the rise of a quick, active, north country trout comes upon me like an emergency for which I am unprepared.” His wet fly list is not so different from his dry flies, including wet versions of the Black and Orange and Red Quill, March Brown, Black Pennell and of course Greenwell. I wonder if modern fans of Greenwell’s Glory appreciate that it was originally invented and used as a wet fly.

During July and August, understandably enough, Grey turned his attention away from the chalk streams to the north and to sea trout “…a wild mysterious animal without a home.” He makes a point that first it is necessary to find if sea trout are actually in the river and, if so, exactly where. (“Good, very good” a previous owner of my copy of Fly Fishing has pencilled into the margin here at some time during the 1930s. I can guess these words chimed with the reader’s experience.) Grey is on less certain ground with his chapter on sea trout, which was usually considered to be a separate species at that time. He believed they fed on flies in the river. He didn’t fish at night and his experience seemed to be confined to Scotland. On the other hand he is very interesting on fishing lochs and voes in Shetland. Generally, when fishing for sea trout in larger Scottish rivers, he confesses a tendency to be distracted by the salmon and grilse which were also present. His sea trout flies were Soldier Palmer, Woodcock and Yellow, Black and Orange Hackle and Black and Red Hackle.

Grey concentrated his main salmon fishing in the months of March and April when the springers were running. He never claimed to be a very successful salmon angler, once fishing 28 days for two fish, one of which was foul-hooked: “…sheer unrewarded toil.” This sounds rather like modern times, but was in fact a run of bad luck and he usually had better results. He also remarked: “…the play of a fresh-run salmon is very fine; I wish it was a little less stately.” That is an honest description and “stately” is a good word for some salmon when hooked; in reality there are at least as many sloggers as hot ones. Obviously we hear nothing about greased line methods in a book published in 1899; for Grey the skill in salmon fishing lay in being able to cast a long and straight line down and across and having a very good knowledge of the lies in each pool. He also wrote that the best time to get a salmon is as the river begins to rise, even if the window of opportunity lasts only for 20 or 30 minutes. I don’t think he was mistaken about any of that. His salmon flies were Jock Scott, Wilkinson, Black Doctor and Torrish.

We have some descriptions of stocking experiments, with American brook trout and rainbows. The chapter on tackle, discussing greenheart versus split cane, nets and gaffs is not so interesting today. In a final chapter entitled “Early Days” he gives an account of fishing border country burns with a worm for tiny trout when he was just 7 years old. In fact there is a good deal about fishing what we would call wild streams, and I would bet the writer was still prepared to use a worm although he complains that “old age” had made him too stiff for the creeping and crawling involved. He was then just 40! There are some accounts of introducing the dry fly to the highlands, fishing the Dart in Devon and a limestone river in Ireland which I think must be the Suir. Towards the end he mentions he was then reading Kenneth Graeme’s The Golden Age, which reinforces the idea that in adulthood and through the sport of angling he was looking to recreate childish joys.

Grey on dry fly fishing

Grey on dry fly fishing  Grey's flies

Grey's flies  Hampshire water meadows in Grey's book

Hampshire water meadows in Grey's book Grey was superseded by Balfour at the Foreign Office in 1916, but not before he had signed the Sykes-Picquot Agreement carving up Ottoman possessions in the Middle East between British and French spheres of influence. For this and its consequences, with which of course we live today, and also some pre-war decisions including his Balkan policy, history has not treated his diplomatic legacy with particular kindness. Asquith once said of this essentially gentle man that he would have gone further if he had not been so interested in fly fishing. (I seem to remember my mother used to say similar things about me). Nevertheless Grey was at one point considered for the Prime Minister’s job, although he showed little personal enthusiasm for it. He was made President of the League of Nations in 2018, and later was appointed Ambassador to the USA, but by this time his eyesight had deteriorated to near-total blindness. He eventually retired from public life and died in 1933. Grey’s private life remains slightly mysterious. His first wife, with whom he shared his passion for the countryside, lived with him in a cottage near the Itchen and was killed in a motoring accident in 1906. He was also widowed from a second marriage. Neither of these marriages produced children, but he is rumoured to have fathered two children from illicit affairs.

As an angler, the last we hear of him is on the Officers’ Fly Fishing water of the Salisbury Avon, where due to his blindness he was permitted by special concession to fish down and across, feeling for the takes. He was accompanied on that day by a young keeper, Frank Sawyer, who had also recently been out with Lord Allenby, the British general who had taken Jerusalem and Damascus from the Turks. Grey’s shyness, judging by his book, seems to have been real and certainly not the “backing into the lime-light” behaviour TE Lawrence was sometimes accused of at the same time. I imagine Grey would have been grateful for the solace of just being by the river, even if he could not see it.

Christmas approaches and it’s a time for buying books! My copy of Fly Fishing is one of the rather ornate Haddon Hall series, the second edition of 1899, and the fly leaf shows that somebody in the Nottingham area received it as a Christmas present in 1937. I don’t believe it has been reprinted recently, but the internet should turn up an older copy or Coch y Bonddu Books have a presentation leather-bound edition at 75 pounds if you really want to treat yourself for Christmas!

Working from home is not too bad...it's a matter of self-discipline really.

Working from home is not too bad...it's a matter of self-discipline really.  High water at Dayhouse weir - KL from bristol

High water at Dayhouse weir - KL from bristol  Wyebank

Wyebank The Grayling Society have a new initiative to gather as much information as possible about grayling catches around the UK. This is not restricted to Society members, but instead all are encouraged to contribute. As our border region is quite an important centre for grayling angling, any information received from it will be welcomed by the Society. The stated purposes are to use the information for research, for conservation of the species and in campaigns to improve water quality. Catch returns will be treated as anonymous and can be made by going to www.graylingsociety.net , clicking on catch returns and following instructions.

November can be a good grayling month and Wales should be open again; although the days are short, let’s hope for tight lines!

Oliver Burch